Autumn Gear Guide

Find inspiration in our Gear Guide that will keep you out on your bike through wind or rain.

Download NowProtected intersections – long a fixture in Dutch urban design – arrive to increase cycling safety in four US cities.

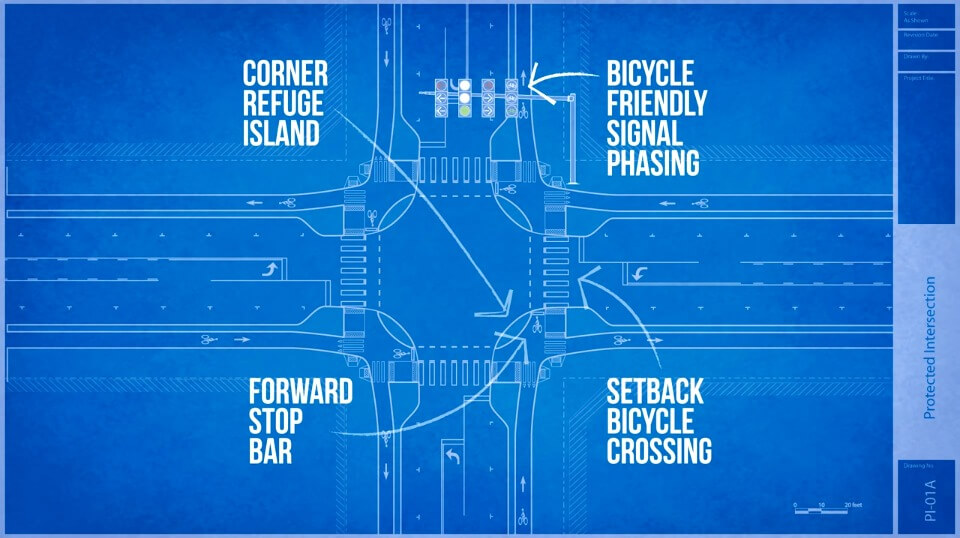

Screenshot from Nick Falbo’s Protected Intersections explanation video.

“Sometimes, change builds up for years. And sometimes, it bursts.” These are the words of Michael Andersen in a recent Green Lane Project article about the sudden and almost unexpected arrival of the protected intersection in American cities.

In “Four US Cities Are Racing to Open the Country’s First Protected Intersection,” Andersen details the concept’s journey from relative obscurity in North America to an enthusiastic reception in Austin, TX; Salt Lake City, UT; Boston, MA; and Davis, CA.

The concept expands the proven safety features of protected bike lanes into the intersection. If that sounds impossible from a traffic flow perspective, consider that many North Americans thought protected bike lanes would be impossible until New York City built its first one in 2007. When other cities took notice of its success, they followed suit. Between 2011 and 2014 there were 113 new protected bike lanes constructed in the US and the momentum shows no signs of stopping.

The concept – a staple of Dutch urban design– was first introduced to American transportation professionals by Dutch writer and videographer Mark Wagenbuur with this video:

Andersen writes:

“It was a tour de force of simple explanation. Then something strange happened: nothing.

Though U.S. bikeway professionals enthusiastically passed Wagenbuur’s video around, and though the ideas could have been applied even to intersections with painted bike lanes, they weren’t.

Maybe it was Wagenbuur’s light Dutch accent, sadly alienating to some U.S. ears. Maybe it was the description of the intersections as “Dutch.” Maybe the country just wasn’t quite ready for the idea.”

Meanwhile, Nick Falbo – video game designer turned urban planner and recent hire at the Portland-based Alta Planning + Design – began pushing for the idea as well. Working in his spare time for a design contest associated with George Mason University, Falbo took the Dutch Junction concept and examined how it could be applied to US streets in a way that would resonate with US city planners. Andersen writes:

“Falbo was watching the success that another Dutch concept, physically separated bike lanes, seemed to have after advocates stopped referring to them as “cycle tracks” or “Dutch infrastructure” and started using the more intuitive “protected bike lanes.”

Coming up with four basic components of protected intersections – a corner refuge island, a forward stop bar, a set-back bike and pedestrian crossing, and bike-friendly signal phasing – Falbo applied the concept to a dangerous intersection in Portland and released this video to a few online forums in February of 2014:

The reaction was instantaneous. BikePortland picked it up, followed by People for Bikes, Streetsblog, and Wired. Within 15 months, Austin, Davis, Salt Lake City, and Boston had all formalized plans to build protected intersections. Austin’s bi-directional protected intersection is already on the ground in a planned housing development, it is simply waiting for the riders to move in.

Almost overnight, the Dutch junction was back in the US urban design conversation again because Falbo had offered language with which to talk about it. Speaking in June, he explained, “Until that video came out, there was no standard name for the design — you heard ‘Dutch junction,’ ‘Dutch design.’ Suddenly the designers and engineers could refer to the ‘corner refuge island’ and talk about it … You give it a name and you let people talk about it, and suddenly they can have conversations that they couldn’t really have before.” Andersen elaborates that, along with the language, the visualization enabled people to fully understand the usefulness and feasibility of a concept which is otherwise too unfamiliar to grasp:

“Change required engineers to understand the details. But it also required non-engineers to understand what to ask for, and why to be excited about it.”

This is a common pattern in bike advocacy. When the language used is unfamiliar or antagonistic, it creates a climate of at best, disinterest, and at worst, hostility towards the very ideas it is attempting to champion. When it is used effectively, language can flip the script – literally and figuratively – on the outcome of the debate.

Related – How to End the War on Cars

When protected bike lanes were first considered in North America, they were frequently referred to by the European name, “cycle tracks”. Just that short linguistic jump was all that was needed to render them too unfamiliar for many planners and residents. Only when they became “protected bike lanes”, more suitable for North American parlance, were they readily accepted.

Following that logic, Falbo tweaked the discourse around the Dutch junction to make it familiar to American bike advocates and urban planners. As soon as they can relate to the conversation, it becomes much easier to visualize how they can find a role for the idea in their cities.

Building on the success of the protected bike lane, the protected intersection is the logical next step in the transformation of US cities into livable cities where pedestrian and cycling safety is included in the urban planning agenda. It’s a race between four cities at the moment, here’s hoping for more contenders in the near future.

To read Andersen’s article in its entirety and find out what each city is planning for protected intersections, click here.

Find inspiration in our Gear Guide that will keep you out on your bike through wind or rain.

Download Now

Comments are closed.