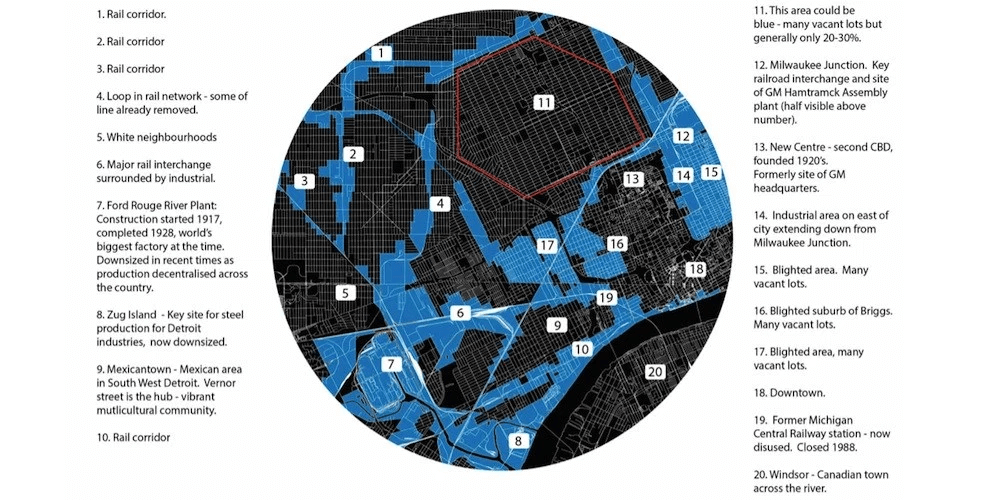

A 9.3 mile (15 kilometer) circle of Detroit, MI. Blue map rendering by Cyclespace.

There’s a lot of excitement around urban cycling these days. According to the 2015 Menino Survey of Mayors in the US, 70 percent of them would take lane space from driving and parking and reallocate it for bicycling. The last time anything like this happened – space between buildings in the centre of town got reallocated – it was to give vehicles more space and a few years later we got urban sprawl. Back then, the reallocation of street space was a sign that something much bigger was afoot.

People were ready for a bold, new experiment in spatial production. They were ready to live on what had been farmland, pay fortunes for transportation, start shopping in malls, get rid of their raincoats, …etc. A buzz first evidenced by the width of the carriageway created a reorganization of everything from school boundaries to the size of our pantries.

So far, the majority think the buzz around bicycling is leading nowhere. (1) It’s a minority mode. (2) Infrastructure spending should go toward everything else. (3) Urban cycling is unlikely to give rise to a unique brand of urbanism – not when its patrons seem happy in housing from the era of the railway or streetcar. And yet, this is familiar. Before the Second World War, motoring enthusiasts felt excluded in the same three ways.

What really differentiates the proto-car-centric period from the proto-bike-centric period we’re living in now is that in the 1940s and 50s cities only had one way to grow: outward, on greenfields. Instead, population growth now has been able to be absorbed by city centres. Depopulated workers’ housing and manufacturing districts from the Industrial Age have been ripe for gentrification. Who by? Hipsters, ageing hipsters, urbanists, creatives, yuppies … all labels for people who cycle.

But what next? Gentrification has happened. The Meat Packing District in New York, NY shows how the game ends: Movie stars and foreign investors have bought it all up and only live there part of the year. In cities where the industrial cores are much smaller, high income folk have taken over the inter-war suburbs. The only place left for the bicycling demographics to move are suburbs from the 1950s and later when housing started reaching into the hills and over horizons.

With the exception of fitness nuts – bless their sweat-wicking socks – few people will cycle if their suburb is hilly or sprawling. Adding e-bikes to the equation can bring a few more on board. Still, we’re hardly redeeming the suburbs.

The question is where do we go to from here with our cities? Do we leave the big ones and move to regional centres? Create new centres in the suburbs, linked via subways? Resign ourselves to confinement within our small, urban village?

All are poor options and none properly factor in bicycling.

Did you know that a 9.3 mile (15 kilometer) diameter city, if it were as dense as Manhattan, would have a population of 6 million people? And did you know that if it were designed around cycling – the way, say, Houston was designed around driving, or how Venice was designed around boats – and if no vehicle were allowed in that city that impeded the smooth flow of bikes, that the average commute time would be faster than in any other city that size? This was one finding from a design research project I ran. I’m now in the process of disseminating these and other findings to my colleagues and bike transportation enthusiasts.

It’s pie in the sky stuff. With that research project, in a university context, we had time to design spiralling apartment buildings and ground planes that dip to help riders speed up and rise so they can slow down without braking. Sound crazy? Consider this then, that architects and engineers in the 1920s were imagining cloverleaf intersections, buildings you could drive into and park your car in, and cities spreading out into the countryside. All of these were unimaginable to everyday people but exciting nonetheless. To participate, they would just need one of these automobile thingamajiggies that radicals of the time were driving to town.

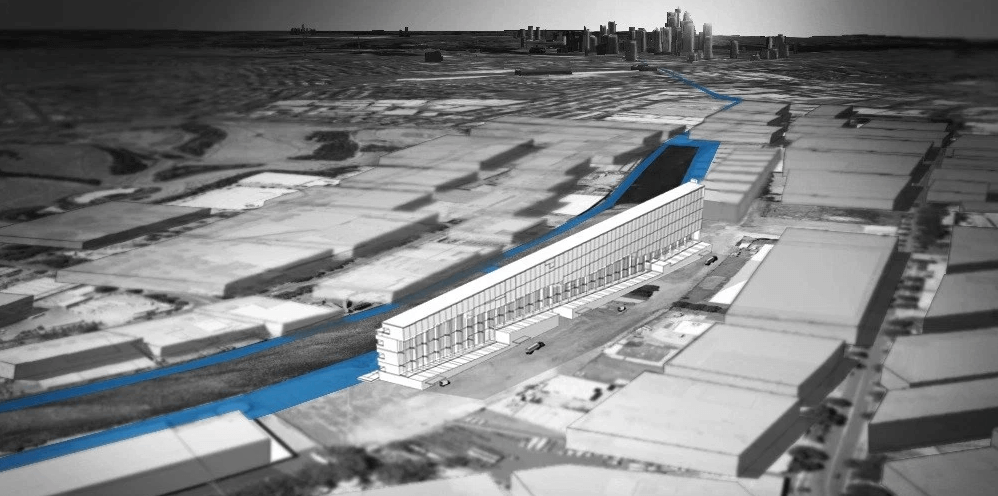

A Cyclespace design of non-vehicular easements that can be made into greenways.

Today, we are those radicals. Whether with our rain-beading trousers or cargo bikes packed with designer-garbed children, we are the firebrands of our cities – not in a way that is faddish but in a profound way. We’re reducing car lanes and parking.

The question is: Can we sustain the momentum? Trends need fresh angles just as fires need logs once the kindling is burning. It would be good if one day cycle-chic, protected bike lanes and everything else the cycling renaissance has added to the urban landscape, were looked back on as the kindling that came before the big log. What will that log be? What could be our answer to suburban sprawl, the thing that cemented car culture by making the car more than just something people were keen on, but something they could not live without?

It’s not widely known but most of our cities have empty land crying out for a new vision. In all of the cities my office has mapped a 9.3 mile (15 kilometer) diameter circle (within which average trip distances would be around 5 miles [8 kilometers]) can be positioned in such a way as to capture a lot of former industrial sites strung along disused rail corridors or former industrial waterfronts. Currently, it’s earmarked for glass condominiums over lots of garaging. Right now though it’s cheap. And it’s flat! It needs to be claimed with a development type that will incentivize cycling.

Here’s where I add that the Netherlands has little that we’re able to copy. Most of the country is car dependent. The medieval town centres where driving is useless are the places with the 60 to 70 percent bike modal shares. But they are tough places to live, with rotten bike parking, single-aspect apartments all looking into each other, steep stairs, and building stock that is expensive to service.

Among architects working on housing solutions for the world’s disenfranchised and poor, there is renewed interest in experimental housing types of the 1950s, 60s, and 70s. Some were disasters so were destroyed. Others have become hip addresses and the inspiration for trendy apartments in Denmark and the Netherlands (bicycling gold standards). Their re-evaluation of post-war brutalist architecture is, almost by accident, leading some architects to stumble upon planning arrangements that really can incentivize cycling.

For example, a classic apartment block from 1961, Park Hill in Sheffield (now heritage listed and trendy as hell), has access galleries that lead onto the ground. You can cycle straight out without using a lift. Rare copies of Le Corbusier’s book show the same thing on the cover: a cyclist on an aerial street. The modern counterpart is the multiple award winning 8 House by BIG in Copenhagen finished in 2010, with an aerial street, a promenade and a cycle track which reaches up to the 10th floor.

It is understandable for people to hold prejudices against apartment living if they are accustomed to freestanding houses. It is reasonable too that bicycling, for most, is totally selfish; what should it matter to any of us if there are families in outer suburbs for whom cycling might only work for dad’s work trip?

It matters to us when our cities can’t fulfill their perennial function: connecting all walks of life to exchange goods and labor. The city is a collective enterprise.

If I’m right about cyclists occupying a similar position of influence to the one occupied by motoring enthusiasts before cars got their space, then urban space should be especially concerning to us. Our role in renewing and gentrifying central districts and lobbying for cycle tracks are our warm-ups pre-match, before we turn our attention to brownfield redevelopment.

There are two American cities where bicyclists are already generating demand for what can only be called bicycle-oriented development. In Atlanta, a looping pedestrian/bike trail called The BeltLine, is catalyzing redevelopment projects on the former industrial sites it cuts through. A better example is the Minneapolis Midtown Greenway. When there was talk of light rail running along it, land either side was rezoned for high density living but the light rail never came. Did that diminish demand for apartments? Not in the slightest. Buyers are attracted by the short travel times to the city and elsewhere – not by light rail or car but by bike. Developers soon figured out that a ramp to the greenway would be an essential sales feature.

My thought would be to take this market-driven phenomenon, evident to a degree in all the world’s post-industrial cities, and put it in the big ring – that’s bike speak for changing into high gear.

Dr. Steven Fleming heads the architectural and educational endeavours of Cyclespace, Amsterdam. @BehoovingMoving.

Get your FREE copy of our new guide: Momentum Mag's E-Bike Guide

In this guide we explore some of the different ways an e-bike can provide solutions for different users, outline the different types of e-bikes available, give a briefer on the technological components, and offer some advice on purchasing your own electric bicycle.

Thank you for your submission. Please check your inbox to download the guide!

I love the IDEA of bicycle for the majority of transportation, but in central Ohio it is generally not possible. Most people cannot bike for a variety of reasons: infrastructure, distance, weather, age, handicaps. On a perfect day in our downtown maybe one of 1000 vehicles is a bike and in suburbs, fuggeduboutit except for experienced hardcore types. Even if there is a committed movement by society over several generations there will never be more than a small minority of 20-50 somethings able and willing to bike for transport. I’ve looked at many pictures and videos of Copenhagen and it seems that even there on nice days (which it usually seems to be, I guess those days are also best for taking pictures!)I have vet noticed elderly etc.

Comments are closed.