Autumn Gear Guide

Find inspiration in our Gear Guide that will keep you out on your bike through wind or rain.

Download NowSome might say that New York City hit peak bike boom when it was announced that two iconic bridges would have separated and safe bicycle lanes installed, but listening to those on the ground who have pushed the complete streets agenda for years, it sounds like this big win was not only a long time […]

Some might say that New York City hit peak bike boom when it was announced that two iconic bridges would have separated and safe bicycle lanes installed, but listening to those on the ground who have pushed the complete streets agenda for years, it sounds like this big win was not only a long time coming it is also only the beginning.

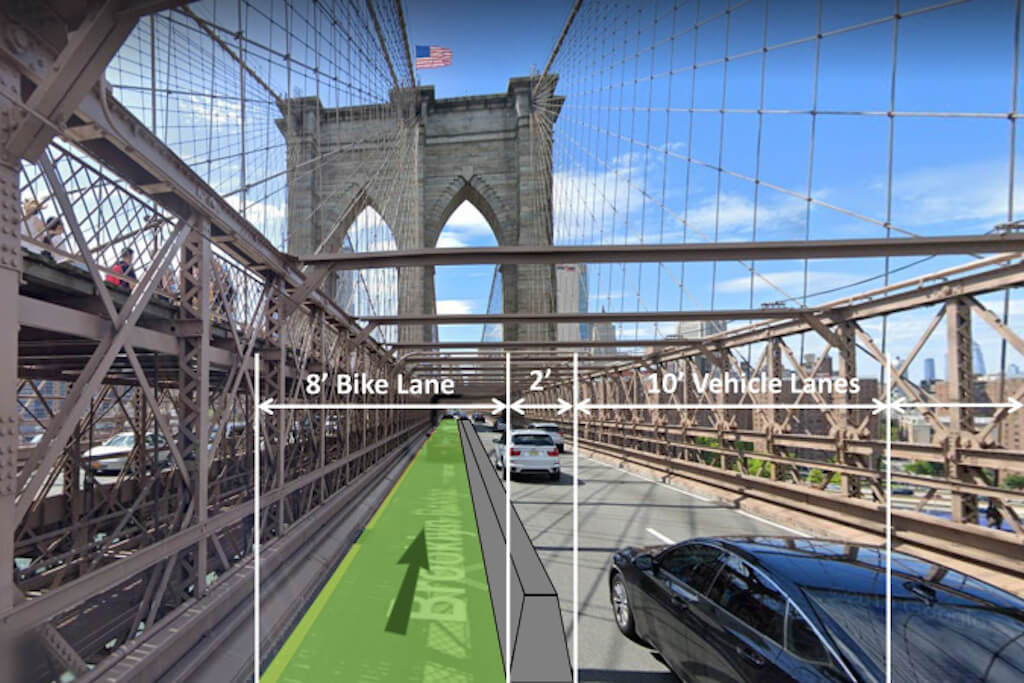

Construction is underway on the Brooklyn Bridge that will take away the innermost Manhattan-bound vehicular lanes to create safe, separated two-way bike lanes, the first reconfiguration on the historic structure since the removal of trolley tracks in 1950. In addition, bike lanes will also be installed on the Queensboro Bridge.

It’s the culmination of years of advocacy work creating safe cycling infrastructure throughout New York City, and it comes at a time when people are discovering the joys of getting around the iconic metropolis by bicycle during the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Bike traffic over the East River bridges is booming. The latest figures show a 27 percent increase over pre-pandemic ridership. A dedicated bike lane on the Brooklyn Bridge cannot come soon enough, and we are thrilled that construction is beginning this month. We will continue to work with the de Blasio administration and the next occupant of City Hall to improve infrastructure for cyclists and pedestrians on bridges across the five boroughs,” said Danny Harris, executive director of Transportation Alternatives, an advocacy group working for safe and equitable streets in New York City.

Currently, cyclists, pedestrians, and especially throngs of tourists alike are crammed onto the narrow and busy bridge promenade atop the structure. And it has caused innumerable headaches. Some cyclists have even taken to singing as a desperate move to clear the way and make it across the bridge.

The project was announced last January in Mayor Bill de Blasio’s State of the City address when he also committed the city to install a record 30 miles of protected bike lanes this year.

From the outside looking in, the announcement was huge. And Juan Restrepo, of Transit Alternatives, agrees because these bridges are not only iconic they are essential.

“These bridges are one of the things you think about when you think about New York City, you think of maybe even like all the shows from back in the ’80s. You couldn’t do like a sitcom-like opening montage without including like a flyby of one of these bridges, whether it’s the Queensboro, Brooklyn, Williamsburg, or Manhattan,” Restrepo says.

“We have a huge city center and it’s all connected to the outer boroughs by bridges. So the bridges are always like such a key way of thinking about the city.”

It’s symbolic of how far the discussion around safe streets and safe cycling infrastructure has come that an idea like this is not only on the table but approved.

“This announcement itself shows just how much the Overton window in the city has changed,” Restrepo continues. “And also how much the needs matrix has changed as well to allow the city to accept that the Brooklyn Bridge needs less capacity for cars and more for bikes and people walking would have been ludicrous thought maybe six years ago. But here we are.”

It’s not like the statistics aren’t there.

According to Transportation Alternatives Bridges 4 People campaign, 19,000 cyclists wheel their keisters across the Brooklyn, Manhattan, and Williamsburg bridges each day. During the height of the pandemic, those numbers were up 55 per cent between November 2019 and November 2020.

“Last spring, New York City was hit by the pandemic in a way that no place else in the United States, and biking and walking, were the only ways to get around,” says Blythe Austin, a volunteer co-chair of the Brooklyn Activist Committee of Transit Alternatives.

“And cycling was also an easy way for people to get exercise. And we had done all this work to build infrastructure. And demand just skyrocketed. Lots of people who had never had the time or the inclination to get around the city by bike suddenly realized that that was a viable thing.”

Restrepo adds that was is happening now also dates back to the impact of Hurricane Sandy that hobbled the city’s mass transit system and made it difficult to drive by car.

“People were picking up bikes as a means for getting around. And a lot of folks who did that sort of kept doing it afterward, because they’re like, oh, this is cool. I didn’t have much incentive to bike around beforehand. But after trying it, I kind of get what people are talking about,” he says. “And I think we’re seeing a lot of that right now, with people who may be opting out of either a car or transit and they are opting into biking as a way of controlling their commute more.”

The two bridge bike lane project caused such a stir, that safe street advocates from San Francisco wanted to get in touch to work a similar transportation initiative in California.

That group was facing a struggle that was similar to another fight in New York City over the Verrazano Bridge.

It goes like this, some may have heard this before. Community activists want change and suggest a workable, fast solution. Take a car lane, convert to separated two-way bike lanes. Done. In comes another very expensive idea to build onto the side of a bridge and leave the precious automobile lanes in peace. Years go by, momentum wanes and the project is quietly shelved. Sound familiar? It does to Restrepo.

“We have seen this on the Verrazano Bridge, where it’s one of the big connectors between South Brooklyn and Staten Island. Without it, there’s no way of getting off the island on a bike,” he says. “So it’s very important to people who are in that area. They’re fighting for a classification of a lane off the Verrazano Bridge, the MTA instead provided an extreme, overtly expensive proposal to add a lane off the side of the bridge. And it’s the same thing that they’re doing in San Francisco, where advocates are asking for a lane off of their bridge and elected officials bought into the idea of, well, let’s study a $100 million-plus project to add a lane off the side of the bridge.”

The strategy is not only underhanded and bound for failure, it also fails to grasp the obvious. That the time is now to secure this vast number of new cyclists and keep them out of their cars, keep the greenhouse gas emissions out of the air. It’s like a win-win scenario on steroids.

“I think with regards to biking infrastructure the bike boom is now you know, like, not five years from now, not 10 years from now,” Restrepo adds.

“And it’s like, how do you push city officials to be responsive to the needs of people at the right moment to capitalize on that moment, versus just allowing them to kind keep grinding their gears and just like kind of wait it out until all of the enthusiasm and the moment has gone. I think a lot that’s the pressure that we kind of felt for Bridges 4 People campaign and the Queensboro Bridge campaign. Like we have a moment here. We’re not going to let them sell us a bill of goods for something that’s 10 years down the line.”

Of course, the time is not now for the Queensboro Bridge, which is not slated for separated bike lanes until next year, despite the pressing need right now, according to Austin. In addition, she highlights the importance of not building these projects in isolation, but considering the network and fill in the gaps to provide a safe trip for commuters from start to finish. That’s the only way this massive growth will not only last but continue to escalate.

She cites the issue of the Pulaski Bridge, which connects Queens and Brooklyn to the outer boroughs and had bike lanes installed. Wrongly, the areas around the ends of the bridge did not have safe cycling and pedestrian infrastructure. Enter mayhem. Finally, the chaos and tragic loss of life was enough to convince the mayor to redesign.

“We try to focus our advocacy on it can’t just do things in isolation, you have to think about the broader network. And that really is is a change that we’ve made in our advocacy in recent years, where I think a lot of times grassroots advocacy in this area started with a bunch of people who were neighbors coming together and saying we want our street redesigned, right?” Austin explains.

“We’re trying to take the advocacy to the next level of pushing for changes at a broader level. Because again, the network is only as safe as the weakest link. And so we need to think about every link in the chain and how people are getting a route and how they can best be served by our streets.”

And that strategy plays into Transportation Alternatives’ current campaign around the upcoming New York City election called NYC 25×25.

It calls for 25 per cent of New York City streets, whether it is for parking or driving, to be given over to more equitable, people-centered projects by 2025. It’s ambitious, but for a city finally making some gains in terms of not only safe cycling infrastructure but also other complete streets initiatives, momentum is on their side. Not surprisingly, Restrepo says all the front-running mayoral campaigns have signed on to the pledge.

“It speaks to how much the Overton window in our city has changed that,” Restrepo says. “It’s going to be revolutionary once the policies are actually put in and you see how that 25 per cent of space is going to be used and how people will come to like it in the same way that the growth of people who like bike lanes, pedestrian plazas, and whatnot has grown over time as these things have been implemented.”

New York City isn’t putting together any radical changes akin to a city like Paris, France just yet. But with the big bike lane victories for the Brooklyn and Queensboro bridges, the 25×25 campaign influencing the upcoming election, it seems the Big Apple is certainly having a bicycle moment, and not a moment too soon.

“It’s a wonderful win, and we need to celebrate it,” Austin says. “And as I said, I think it signals a cultural shift, but it’s just the beginning of what we’re looking for.”

Find inspiration in our Gear Guide that will keep you out on your bike through wind or rain.

Download Now

Leave a comment