Picture this: it’s Monday; you’re embarking on your ride to work. You hop in the saddle and pedal out of the garage, four blocks down your residential street, then 15 blocks down a traffic-calmed back street – tree-lined and tranquil. As you approach downtown, you turn into the City’s new protected bike lane, the last two miles (3 kilometers) recently installed to complete a network from your neighborhood directly to the business district. The lane is buffered by planters and the subtle scent of flowers tickles the air. You arrive at work and lock your bike up in the bike locker without having to lift it, strolling into the office energized and ready for the day.

Now picture this: it’s Monday; you’re embarking on your ride to work. The whizzing of fast-moving cars and transport trucks is an assault on your sleepy senses as you carry your bike down the steps. You hop in the saddle and head off down the sidewalk, where you’ll remain for 15 bumpy blocks until it abruptly ends, throwing you onto the barely-existent shoulder of a 50 mph (80 kph) arterial road. You ride over cracked asphalt and broken glass, swerving narrowly to avoid potholes and road debris, while motorists lay on their horns as they pass you by a margin of a foot. When you’re finally able to leave the arterial road after what feels like the narrow escaping of death, you take sidewalks and back alleys for the remainder of the ride. You arrive at work, lock your bike to a fence, and pray it’ll still be there when you get back. You get to work stressed but alive.

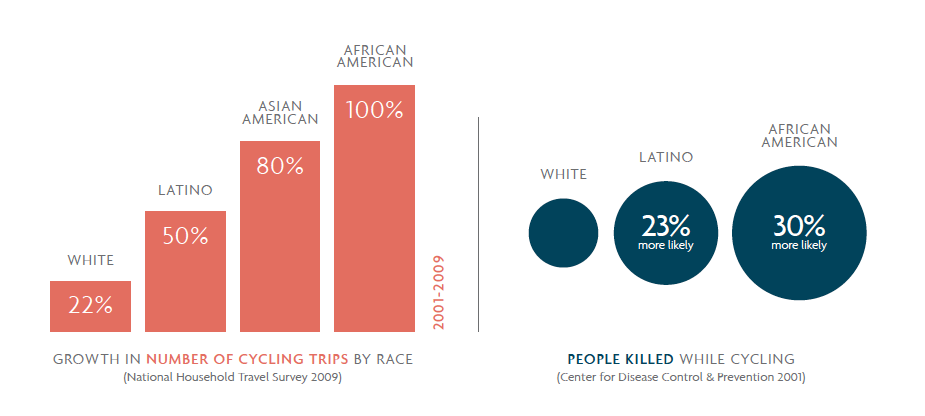

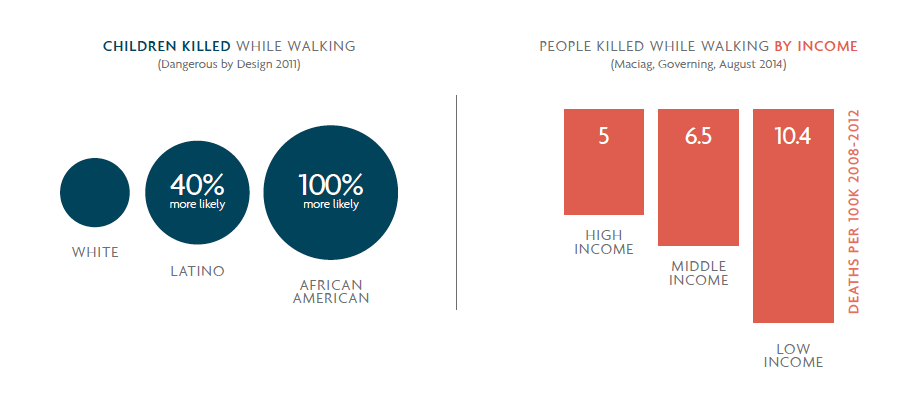

Unfortunately, this stark contrast in the relative safety of cycling is the reality across the US. Like many of America’s divisions, its boundaries are drawn along racial and economic lines. In predominantly white, upper-income regions of many cities, residents enjoy car-free plazas and protected bike lanes designed to encourage and enhance the vitality of their active transportation (walking, bicycling, skateboarding, etc.) communities. In the very same cities’ poorer regions where the majority of residents are people of color, many streets don’t even have sidewalks or crosswalks, let alone a bike lane.

It’s an imbalance that has devastating social consequences. A safe, strong, biking and walking community produces significant social gains – reducing health disparities, significantly lowering household transportation expenses, creating jobs and providing access to employment, lowering air and noise pollution, reducing mental health problems, and reducing violence by improving social cohesion. When people are excluded from being stakeholders in policy-making and infrastructure planning, they end up with less access to safe cycling, and are in turn denied its social gains. The tragic irony of the situation is that the communities who could benefit the most from cycling are the same communities being neglected in the planning process. This neglect only inflames and entrenches existing inequalities.

“Those who stand to gain the most from increased bicycle usage are the communities that are the most disproportionately impacted by violence, health care disparities, and unemployment,” said Oboi Reed, co-founder of Slow Roll Chicago – a non-profit organization which uses social bike rides to foster positive social change in Chicago’s Southside and Eastside – and recognized by the White House as a Champion of Change. “These are, in our cities, communities of color and low-moderate income communities.”

Reed is part of a groundswell of grassroots advocates changing the face of bike advocacy across the US. While the mainstream movement has traditionally been dominated by mostly white, mostly male, mostly upper-income individuals, a new generation of advocates is pushing for diversity and inclusion to sit at the front of the movement and make social equity the primary goal. So what is equity anyway and what does it have to do with bicycling?

Equity vs. Equality

Equity is a commitment to fairness and justice. In contrast to equality, equity acknowledges current socioeconomic variances among the communities it’s attempting to support. So while a policy of equality would deliver the same resources to everyone regardless of their circumstances, a policy of equity delivers different resources to different people according to their varying needs. “What we look at when we talk about bicycle equity is who needs the most and who stands to benefit the most,” Reed explained. “When we frame it up in terms of cycling, what we say is, those who bike the least need the most bicycle resources in order to help them bike more.”

In marginalized communities where safe cycling infrastructure is scarce if it exists at all, the government should be investing more in bike programs and infrastructure than it does in communities where the groundwork has already been laid. Any program that does otherwise at best maintains socioeconomic imbalances – and at worst intensifies them.

Dr. Adonia Lugo, an anthropologist who studies bicycling in Los Angeles, CA and around the country, believes a meaningful approach to equity also requires developing a broader understanding of the cultural variances within the bicycle community itself. “I would say that bike equity refers to having more of a balance in terms of who’s creating representations of bicycling and who’s influencing bike policy, and tying that more to who is currently using bicycles,” she said. “That will have inclusive effects in terms of who we want to see riding in the future.”

When the majority of Americans biking for transportation are low-income people and people of color but the majority of American bike advocates are upper-income white people riding for recreation, there’s a strong potential for the needs of many to be misunderstood by the few who are supposed to be representing them.

Over in Philadelphia, PA, the Better Bike Share Partnership has been at the forefront nationwide for their efforts to build equity into public bike share. Bike share systems in general have been plagued by accusations of social inaccessibility since their start in most US cities, an issue which Better Bike Share is making great strides in overcoming. Katie Monroe, who conducted outreach for the Better Bike Share Partnership through the Bicycle Coalition of Philadelphia, focuses on building authentic relationships with individuals in communities she’s working with. “I think, really critically, it isn’t just trying to recruit more women or more people of color, or more low-income people to an existing agenda,” she explained. “It’s about letting the perspective of the people that you build authentic relationships with inform the agenda.”

“You have to do much more than open the door,” Reed elaborated. “You have to create a safe, protective environment where people who haven’t felt traditionally a part of this community want to participate and feel safe in doing so, feel valued, and feel embraced in being there and expressing their voices and concerns.”

Who Wants to Bike?

As policy-makers wake up to the need to be more equitable in their transportation planning, another set of problems arises. When mostly white, upper-income bike advocates push an agenda for increased cycling infrastructure in mostly low-moderate income communities of color, they are sometimes surprised to find they’re not welcomed with open arms. While building bike infrastructure is often thought of as a surefire method to attract more people to bicycling, the reality is that not everybody wants to ride, bike lanes or not. “I think there’s this belief in bicycle advocacy that infrastructure has this power to produce new users, that suggests that people have a much more uncomplicated relationship with transportation than they actually seem to,” Dr. Lugo said. “Transportation is a heavily emotional, heavily status-oriented thing.”

For decades, the private automobile was the ultimate American status symbol. Obtaining your driver’s license marked the passage into adulthood and independence and car ownership was a way to say to the world, ‘I’ve made it.’ The perception that somebody who rides a bike must be doing so because they’re poor is a barrier to many people of color and low-moderate income people riding, who are seeking to avoid the stigma of poverty. “People who have been marginalized and disenfranchised, we’re aspirational,” Reed explained. “We want to express to ourselves and to the world who we are and what we’re about, because so often the world can have this perception of who we are that’s inaccurate…something that doesn’t do that is something that we’re careful about.”

While Reed and the Slow Roll community have seen moderate success in changing the perception of bicycling in their neighborhoods, he acknowledges how much work there is left to do and how difficult that work can be. Unseating a deep, decades-old cultural norm is not something that can be done overnight.

Beyond social status, there are other issues at play that make toppling the car’s reign all the more difficult. If you look at what Americans use their cars for, it often isn’t to drive quickly over long distances. In fact, 50% percent of all trips made by car in the US are under 3 miles (5 kilometers), and include many trips that could easily be covered on a bike or on foot.

Dr. Lugo believes the supremacy of the automobile has less to do with convenience and more to do with a historical desire to segregate and separate. The car was a key facilitator of suburban flight – which we’ll return to in a minute – and still enables many people to travel through town unburdened by the threat of having to interact with anybody else. For many women and LGBTQ people, traveling outside of a vehicle can present a perceived or very real risk to their safety. In low-income communities where street violence is more prevalent, these risks are amplified.

For others, it’s simply a desire to control their surroundings as much as possible. “I don’t think we’re necessarily going to be able to address the enduring status of car ownership until we start to look a little more directly at why it is that we’re so horrified at the thought of spending time together,” Dr. Lugo said.

While the complexity of these issues cannot be overstated, some optimists are hedging their bets on the bicycle’s capacity to at least make a dent in tackling some of the obstacles. However, if bicycle equity is to be successful, it needs to be about more than only building infrastructure, but building trust as well.

“Bike Lanes are White Lanes”

Malaika Sharpe, a massage therapist and long-time cyclist, years ago saw her own community in Portland changed unrecognizably by gentrification. With a foot in two worlds, both an everyday cyclist and somebody who has felt the blow of seeing your community as you know it disappear, Sharpe understands the fears and frustrations of many communities of color when confronted with bicycle infrastructure.

“One of things that has become very clear, through many cities throughout this country now, is that with a bicycling community moving in, there’s usually new people coming in to neighborhoods that are more densely populated by communities of color,” she explained. “Housing is usually less expensive, so folks who have been there for a while and made their way and feel comfortable, are now being displaced by things that they don’t even recognize as being a part of their community.”

The perception of bike lanes as an express route to gentrification is widespread, and not entirely unfounded. The history of American transportation is inextricable from a history of racist and classist planning policies that actively separated and marginalized minority and low income communities. When a lot of people began moving out of cities in the 1950s and 1960s, miles and miles of urban freeways and arterial routes were constructed to shepherd middle-upper income, white people out to the suburbs where they could escape what they saw as the social ills of the city. Almost uniformly, these roads were routed through low-income communities of color, sometimes slicing them in half with an uncrossable highway or a maze of overpasses and bridges – sometimes bulldozing them entirely.

Now the tide of white flight seems to be reversing; upwardly mobile young people are moving back to the city in droves. Arriving alongside a slew of artisanal cafes, boutique clothing stores, and bike-friendly microbreweries, this young creative class is now displacing the same communities who had already been displaced by white grandparents heading in the opposite direction. For many communities of color, the green paint and flower boxes of an incoming protected bike lane don’t represent positive progress, but the foreboding sense that history is about to repeat itself on two fewer wheels.

“Equity doesn’t exist if I’m not there,” Sharpe said. “If you chase me out, if you chase out anything that tells me who I am, what’s equity? I have to value it for it to be of benefit to me.”

Pedaling Forward

If bicycling is going to be successful as a pivot point for social change, it’s going to require some hard conversations about its impacts – both positive and negative. One can be optimistic about the future of biking in the US, while remaining mindful of its history and its limits. “We can’t go into this work with this idea that, ‘Ah it’s not true, we build bike lanes for everybody it doesn’t matter what people think,’” Reed said. “No, what people think is real. So if we want people of color and low-moderate income people to embrace the activity of cycling, then we have to acknowledge how they feel about this stuff.”

Both Reed and Sharpe said that if bike ridership is going to increase in low-moderate income communities of color, then the majority of the push for change will need to come from within those communities. “We as people of color, we have to create a culture of cycling in our neighborhoods that allows us to express ourselves, that allows us to use bikes as a way to speak to who we are,” Reed explained. “When we own the activity of cycling, it’s no longer somebody else’s activity, it’s no longer a white activity, because we feel connected to this activity and we own it like any other community does.”

For advocates and bicycle riders from outside those communities, there is still a big role to play. “One thing a lot of bicycle advocates could do is develop more awareness and educate themselves about other types of bicycle users who are out there,” said Dr. Lugo. Developing real relationships with other communities, as Munroe mentioned, should not be an afterthought but a driving motivation behind any equity work. “The important part is being good partners and being open and listening and letting it inform your work,” she said.

At the policy level, recognize how your own skills and privileges can be used for good. This can go a long way to fill in the gaps many marginalized people don’t have the resources to tackle. Advocating for policy change requires a substantial time commitment – time to make phone calls, send emails, attend council meetings, volunteer at community events, and network with neighbors. For many low-income people who are working multiple jobs and looking after their families, there may not be spare hours to petition the mayor for a bike lane. Those with economic privilege have the opportunity to champion bike equity at the advocacy and policy level as well.

“Stand up for equity. Stand up for the importance of cities and city agencies to make equity a policy priority,” said Reed. “We need allies in this work, it shouldn’t simply be black people and brown people advocating for what’s right, it should be everybody taking a position on this stuff and working for what’s right.”

Hilary Angus is a freelance journalist currently traveling the American west coast by bicycle. She writes about urbanism, sustainability, and the intersection of bicycles and social justice. hilaryangus.com

Get your FREE copy of our guide: Momentum Mag's Cargo Bike Guide

Discover the wonderful world of cargo bikes! Download this comprehensive guide to learn about different cargo bike models, brands, the history of cargo bikes, buying advice, one family's experience with cargo biking, and more.

Thank you for your submission. Please check your inbox to download the guide!

The Relay Bike Share program in Atlanta has done a good job at being equitable at placement locations with their hub stations… recognizing that Bike Share can be a tool to establish equity and inclusion. A great example for the rest to follow.

Great piece. How can we do more to actualize these values? One way is for “white folks” to not just think of people as as low income and/or people of color, but also as part of the working class, who are the vast majority of people in the country. We need more of the Occupy attitude, the 99% vs the 1%. A class perspective clarifies many things, especially for many white folks who think of themselves as middle class, but are really somewhat more privileged workers.

Comments are closed.