Autumn Gear Guide

Find inspiration in our Gear Guide that will keep you out on your bike through wind or rain.

Download NowThe helmet debate has been raging for years. The way things look, it shows no signs of abating.

Three years ago when I was the Bicycle Coordinator in Minneapolis, MN, I became involved in a controversy over a bicycle helmet – or lack thereof. After a trip to Europe, where I had ridden with the non-helmeted masses in three of the safest bicycling nations on Earth – Denmark, Germany, and the Netherlands – I had declined to top my noggin.

Photo by Martti Tulenheimo

I didn’t realize it but I had become one of the first U.S. public officials to question bicycle helmets openly, telling the local newspaper in an interview, “I just want [bicycling] to be seen as something that a normal person can do … you don’t need special gear. You just get on a bike and you just go.”

Locals immediately criticized me. The pro-helmet cry was passionate and full of concern over traumatic brain injuries, which is not unusual when bicycle helmet policy is debated. Soon after, I was told to start wearing head protection while bicycling on the job.

Even though I was no longer able to talk about helmets without the risk of public outcry, the debate was far from over. Some people came out of the woodwork to support my position, including a high school student who published an opinion piece that included research showing the promotion of helmets was leading to an increase in the fear of bicycling. A leader of a mountain biking club for kids also supported the position. He shared his experience of being forced to resign as club leader after he refused to change his view that helmets cause people to stop bicycling for city transportation trips.

That story hit home. Although I was not forced to resign, I refused to change my view and as a result, I largely curbed my penchant for bicycling in the city.

Although we often tout the increase in bicycle commuting that we’ve seen over the last two decades, the reality is that the rate of bicycling in the US and Canada remains very low. In 2014, bicyclists comprised only 0.6 percent of all commuters in America, and only 1.3 percent in Canada according to a 2011 study. As North American bicyclists, this makes us barely noticeable to motorists.

But progress is taking place. Officials and advocates are making smart investments to increase bicycling rates in North American cities: more bike paths, protected bike lanes, traffic calming, and educational training. According to the League of American Bicyclists, those cities that are leading the charge with bicycle-friendly changes are experiencing an increase in urban ridership.2 Cities like Portland and Minneapolis are great examples, with bicycle commuters respectively comprising 7.2 percent and 4.6 percent of residents traveling to work in 2014.

When it comes to bicycle safety however, progress slows when the center of attention becomes the bicycle helmet. Much like whether or not a motorist in an accident was wearing a seatbelt, one of the first questions we ask when a bicyclist is involved in a crash is, “Were they wearing a helmet?” The media and police reflect the public’s pro-helmet sentiment by implying that its role in any major crash is highly significant.

Most health care professionals tip their hat to the helmet as well. In a recent National Public Radio piece titled As More Adults Pedal, Their Biking Injuries and Deaths Spike Too, the leading piece of safety advice given to bicyclists by the doctor and researcher was, “Wear a helmet.”

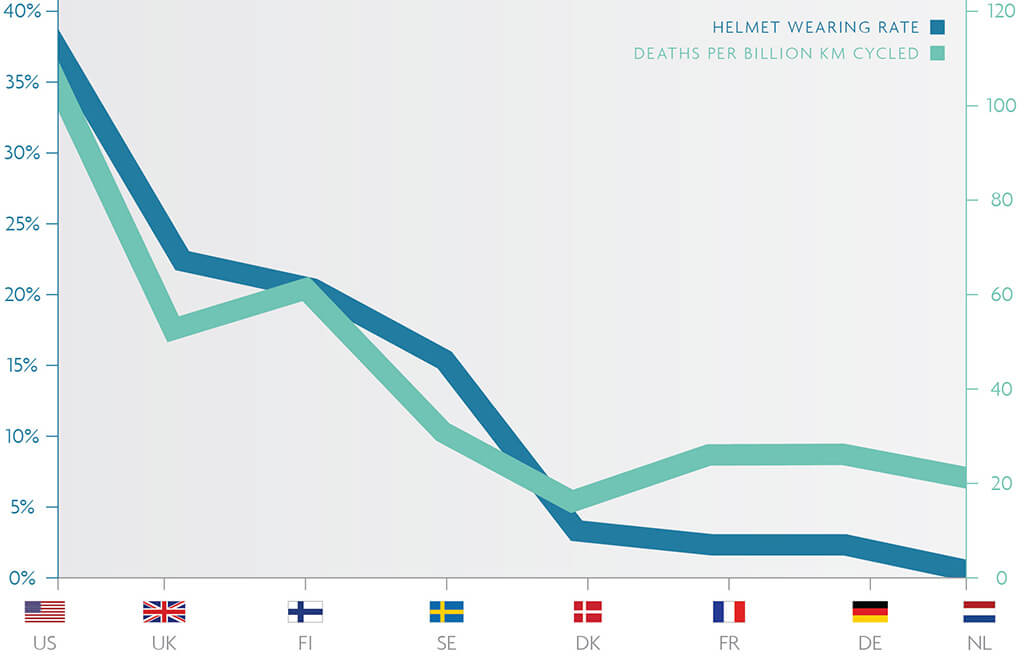

Helmet use’s association with fatality rates by country. The countries with the lowest bicycle fatality rates also have the lowest helmet usage rates. This suggests that bicycle helmets are not necessarily responsible for better safety records. Some researchers point instead to carefully engineered bicycle infrastructure which leads to higher rates of bicycle ridership in a population. cyclehelmets.org

There are studies of every shape and size about bicycle helmets and fair warning: your head will soon spin if you dive in on the Internet.

Its complicated history notably began in the late 1980s, when helmet use was uncommon in the general population. A 1989 study by epidemiologists Diane C. Thompson and Dr. Robert Thompson examined the helmet-wearing habits of Seattle bicyclists who were in crashes and concluded that bicycle helmets reduced their chances of head injury by 85 percent, if the bicyclists were wearing a helmet – a far-reaching claim given what we know today. Just keep reading!

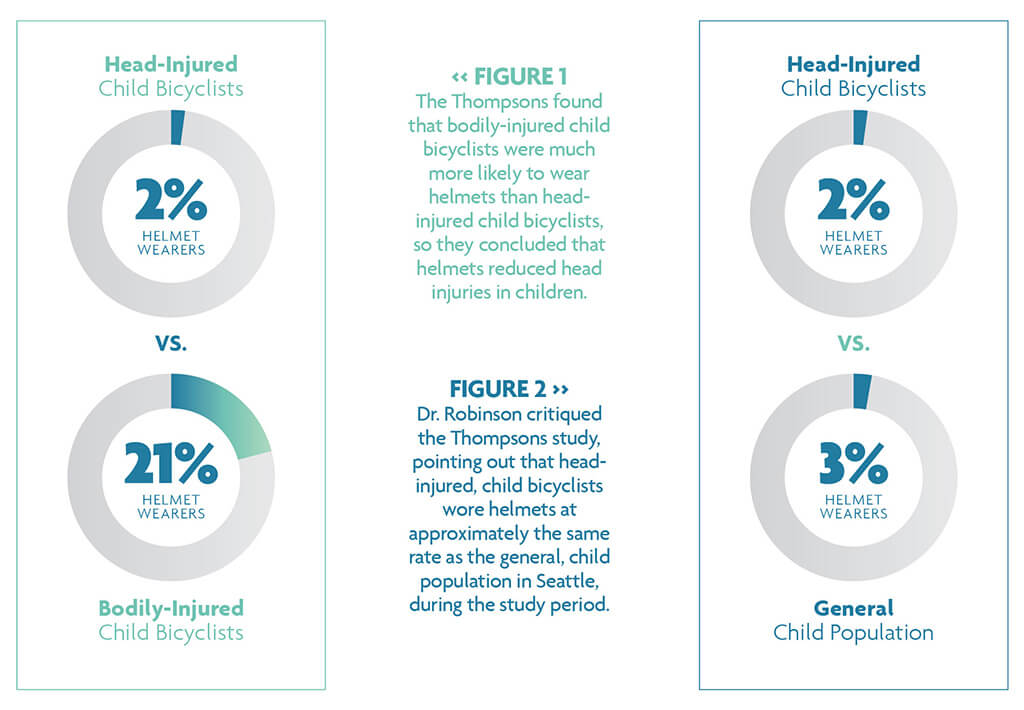

In order to reach this conclusion, the Thompsons compared the low, helmet-wearing habits of head-injured bicyclists with the high, helmet-wearing habits of bicyclists who had sustained other bodily injuries. Because of the discrepancy in helmet wearing rates, with the bodily-injured group wearing helmets at a much higher rate than the head-injured group, the researchers concluded that helmets were greatly reducing head injuries.

But Dr. Dorothy Robinson, a leading bicycle helmet researcher in Australia at the University of New England, criticized their conclusion because of the comparison group used.

“The whole idea of a [comparison] group is that it should represent the general population,” she wrote to me in an email. If the study had used the low, helmet-wearing rate of the general, child bicycling population seen in Seattle at the time, there would have been very weak evidence showing that helmets reduced head injuries.

Why is it unfair for the comparison group to be bodily-injured bicyclists? Dr. Robinson theorized that bodily-injured bicyclists got into crashes more often, because they were wearing helmets. More on what could be behind that later!

In the decades since (even while using bodily-injured comparison groups), no researcher has been able to replicate the 85 percent head-injury reduction rate of the Thompsons study. A 2011 Norwegian meta-analysis by Rune Elvik showed that the average reduction in head-injured bicyclists in all prior bicycle helmet research was 30 percent. This study included the oftentimes overlooked negative effect of helmets on neck injuries, which four studies have now analyzed.

In 2013, the Washington [DC] Area Bicycling Association petitioned the US Federal Highway Administration to remove from its website the oft-repeated statistic, “Helmets reduce head injuries by 85 percent,” since the claim rooted in the ’89 study was providing false security to bicyclists and distracting from real safety measures.

The transportation agency accepted the request. But after conducting a few Google searches, it was apparent to me that the 85 percent figure still persists elsewhere disguised as uncontroverted fact.

Before the Seattle study became out-dated, health care and safety officials were arguing for helmet laws and governments around the world were responding. Australia and New Zealand passed mandatory helmet laws in the 1990s. At first they were touted as a success because bicycle injuries and fatalities dropped.

But researchers led by Dr. Robinson discovered that pedestrian and motorist injuries and fatalities were also dropping and that the decline of all traffic mishaps were coinciding with other more far-reaching road safety improvements, such as efforts to reduce drunk driving and speeding.

Moreover, Dr. Robinson was concerned by a drop in cycling that occurred after the helmet laws went into effect – a drop which alarmingly resulted in a higher rate of bicycle crashes per person. In effect, the reduction in drunk driving and speeding was one step forward for all modes of transportation but helmet laws were two steps back for bicyclists.

Today, proposed mandatory bicycle helmet laws in the US are nearly always dead on arrival and no state has yet passed legislation for adults. This is due to opposition from bicycle advocates who take the position that helmets should not be required due to reduced bicycling levels seen in mandatory helmet-law countries. As you’ll see later, reduced bicycle riding is harmful for many reasons.

Recently in Canada, where half of the country’s ten provinces currently require adult bicyclists to wear a helmet, researchers led by Dr. Kay Teschke at the University of British Columbia conducted a groundbreaking study that examined the effect of bicycle helmet laws. It incorporated surveys of bicyclists asking how often they ride, in addition to their helmet-wearing habits.

Researchers then compared this information to medical data and found that helmet laws had no effect on a bicyclist’s chance of ending up in the hospital with a head injury. Whether a person lived in a mandatory helmet province with an average 67 percent helmet-wearing rate or in a no-law province with 39 percent of bicyclists wearing helmets, the chances any bicyclist would end up with a head injury were no different.

“Years ago, I would have never thought that a helmet law wouldn’t make a difference,” Dr. Teschke told me over the phone. “But over time, I have seen that putting on the helmet causes something mysterious to happen.”

“The data [in studies such as those by the Thompsons] absolutely shows that helmets reduce the chance of head injury for bicyclists who have arrived at a hospital. But the mystery now is, why doesn’t the helmet give you a lower chance of arriving at a hospital with a head injury accident in the first place? The helmet seems to cause us to do something that cancels out their benefits, and we’re not sure what that is.”

It seems obvious if you hit your head on an object, a helmet will cushion the blow. So then why does it appear that wearing helmets has not given us a societal level benefit? For this, we need to take a journey into the world of sports helmets.

Enter Greg Ip, a Wall Street Journal commentator who wrote the book, Foolproof – Why Safety Can Be Dangerous and How Danger Makes Us Safe. He covers many counterintuitive ideas about safety devices, including the football helmet.

The football helmet wasn’t introduced until 1939, more than half a century after football was invented. In the 1960s, when helmets were coming into greater use, Ip writes, “Football related deaths declined but the number of quadriplegics and broken necks went up.”

He continues, “The helmet has changed players’ behavior by allowing them to hit each other with their heads and when that happens the neck and spine form a single axis and the force of the blow is fully loaded onto the spinal column.”

The game of hockey saw similar unintended consequences, after helmets became mandatory in the National Hockey League in 1979.

But in the sport of rugby, where hard helmets are not allowed, the rate of injury and death is lower than football. This is very likely because rugby players have never adopted the hitting energy and velocity of football players.

“Depending upon the activity, a helmet may allow you to take more risk,” Mr. Ip told me in an interview.

So then let’s more closely examine the activity of bicycling. We know that it is different from football and other contact sports in a variety of ways; for one, people bicycle on streets and trails.

Three Basic Theories by Researchers Point Out How Helmets Affect Our Behavior:

Head injuries make up a relatively small number of the total injuries to bicyclists, and on top of that, the likelihood of hospitalization due to a bicycling mishap is quite low. In the 5-year Canadian analysis of helmet wearing by Dr. Teschke, the rate of injury was 633 per 100 million bicycle trips. Viewing this data in a pie chart relays how exceedingly rare it is to be seriously injured or killed on a bicycle. You can’t even detect the piece of the pie that puts you in the hospital:

But even if we take the position that 633 of 100 million trips is too high, only 25 percent of those hospitalizations involve an injury to the head or face.

Because the bicycle helmet is the main focus, citizens and public officials are largely distracted from addressing the bicycling injuries that are much more likely to happen – damage to the torso and extremities – which make up 82 percent of hospitalizations.

Simply put, all of this talk about bicycle helmets takes our eyes off the bigger crisis: injuries to everything south of the noggin.

Researchers sometimes call this risk compensation. A 2012 survey in Norway found that people who rode bicycles at higher speeds were more likely to be helmeted (as well as using other racing gear such as spandex, goggles, clip-in shoes, a superlight bicycle) and more likely to be involved in crashes. Slower bicyclists were not as accident-prone and because they perceived bicycling to be less risky, they were not as likely to wear helmets.1

This finding was backed up in 2013 by a video analysis study led by Mohamed Zaki. Researchers in Vancouver measured the speed of bicyclists at a roundabout, where helmeted bicyclists were found to be traveling approximately 50 percent faster than riders without helmets.2

Even though speeders may have fewer head injuries in the hospital, compared to the non-helmeted bicyclists who end up there as well, we must remember the theory of misplaced concern. They may be ending up in the hospital more often in the first place, dealing with injuries to the rest of their body, in part due to the psychological permission the helmet gives them to ride fast and more dangerously

Since there is evidence that bicycling drops when helmet usage is made compulsory, the total pool of bicyclists drops.

Peter Jacobsen, the most cited researcher regarding this theory, found in 2003 that motorists were less likely to collide with a bicyclist if there were more people riding bicycles – no matter the size of the city, the intersection, or the time of year. Since it’s been shown that helmet laws are associated with a decrease in the number of bicyclists, the safety in numbers theory suggests that when there are fewer bicyclists on the road, motorists are more likely to collide with them.

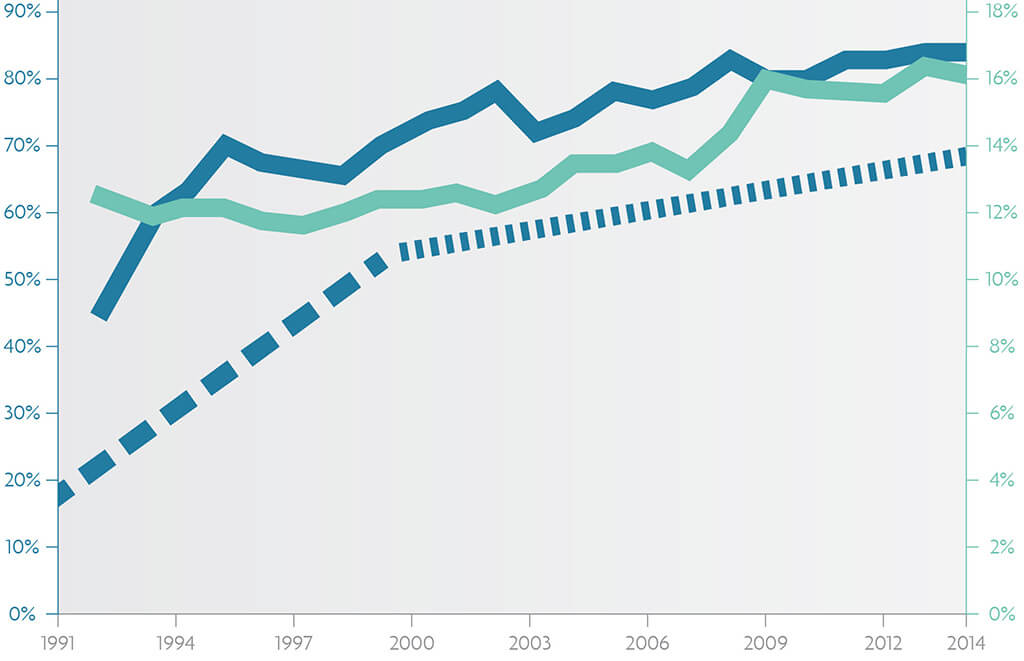

American helmet use compared to the % of head injuries in bicyclists (excluding mountain bikers). As the use of bicycle helmets has been rising in cities such as Portland, the percentage of head injuries that make up all bicycle mishaps has also been rising in the US. This surprising and perplexing association suggests that helmets are like altering our behavior in unintended ways. However, more conclusive research is needed.

Readers know that riding a bicycle is fun. I can tell you where my first $60 in the piggy bank went when I was 6 years old. It purchased a discounted, red, banana seat Huffy and I rode that bicycle up and down our driveway and into town until my knees couldn’t take it anymore!

When adults who haven’t ridden a bicycle since childhood experience it again, they feel a renewed sense of excitement, freedom, and adoration for the bicycle.

We all know that daily activities carry the risk of injury: driving a car, walking down a flight of stairs … but there is scant evidence showing that bicycle riding is any more dangerous than those things. Bicycling is about as safe as driving a car and walking down a sidewalk and is safer than running or playing basketball or volleyball. What sort of message would it send if we had laws or campaigns promoting helmet use in those other daily activities?

We all know that one of the biggest barriers to bicycling for many is the fear that it is not safe, a fear that is perpetuated by questionable research and emotionally charged pro-helmet language: to wit, the ’89 Thompsons study concluded non-helmet wearers would risk “not being able to think or talk because your head has been pounded to jelly”.

Rather than focusing on the dangers of injury, we need to be promoting the freedom of bicycling which gives people the ability to make short trips in cities and towns without having to deal with the headache of parking, traffic jams, and expensive mechanic bills.

Bicycling is also about that mental health boost that we all need on a daily basis. Pumping your legs to get a bicycle moving, gliding down a slope, and feeling the wind on your face is better than any prescription.

We should also be doing everything we can to get more people bicycling: the risk of injury is far outweighed by the health benefits every person gets when they ride and in higher numbers, fewer people get killed! Life span has long been known to increase substantially when people ride bicycles.3 Plus there are numerous community and environmental benefits when more people are bicycling on the road.

Most of us couldn’t be forced to bicycle at the edge of a busy highway or urban arterial street without some form of protection. When the topic of bicycle safety does burden conversation, we should be arguing for bike paths, protected bike lanes, and traffic calming – not focusing on the bicycle helmet.

Teschke argues, “I wouldn’t send my daughter into a bad situation. Any mother or health care professional should be begging for separate space, because that is what our study found actually lowers the chances of injuries. This helmet thing is a huge, huge diversion of very smart people’s time and energy.”

As I was interviewing the Thompsons, they reminded me of what makes helmets so attractive. One of them said, “Helmets are an easy solution to make things safer.”

But now that we are decades into the research, we are learning that the easy solution isn’t always that effective. While carefully engineered bike infrastructure and traffic calming may be more difficult to accomplish, they will do more to improve our long-term well-being than a helmet ever can.

There’s a lesson we can take from the ever-improving aviation industry, which Greg Ip writes about in his book. Airlines are very careful not to talk about safety problems, due to the damage this can cause for their bottom line. But when a safety problem does occur, Ip says, “the law requires the (American) National Transportation Safety Board to investigate the accident.”

This attention to detail results in constant safety improvements and thorough investigations are bolstered by anonymous reporting opportunities. The Aviation Safety Reporting System allows air traffic controllers, pilots, and flight attendants to submit near misses and then publishes their lessons online for everyone to see.

Our goal too, should be improved safety for bicyclists. But we shouldn’t be distracted by one visible device that takes our eyes off of the big picture.

As Ip said in a recent radio interview, “Don’t overuse the tools that we have. Allow a little bit of background risk to take place so that the tools we have remain powerful for the times we really need them.”

He continues, “There is a saying in the safety research industry: Sometimes you want to be a little bit scared … so you’re always aware of what’s out there, and that awareness will create an attitude of more precautionary behavior.”

Next time you ride a bicycle, whether you choose to wear a helmet or not, remember that the bicycle gives each of us the ability to explore our world. We should all be ambassadors for the bicycle and be mostly unafraid to ride it, just as we are.

Shaun Lopez-Murphy lives with his husband on their farm in Wisconsin’s Driftless Region, where bicycles come in handy when the cows get out. He is a transportation planner with Toole Design Group. You can follow Shaun on his Twitter account @shaunmurphywi

Find inspiration in our Gear Guide that will keep you out on your bike through wind or rain.

Download Now

i had a serious crash and if not for my helmet i would be dead or braindead….

I ride my bike weekly in the summer time, I feel naked without wearing one. My helmet is black/bright green neon stripes. I think it helps drivers see me from afar: I always recommend choosing bright colors over black helmets. To me, I look and feel more professional on the road: Where I live I see more truckers and I ride with a life jacket on a long bridges at farm roads. Watch out for alligators…I’m just saying. 🙂

I ride my bike in the Florida about 2 to 3 times a week about 10 miles at a time. I have tried using helmets and it greatly reduces my enjoyment of biking. I would choose not to bike if I had to wear a helmet.

A very comprehensive article which sums up the situation very well. The laws, promotion and propaganda for helmets is based on bad science, but it has been accepted as fact for so long that it is almost impossible to change perceptions, the so-called “persistence of myths” effect. It doesn’t matter how much real science proves that helmets don’t work, people revert to their original belief.

There are two types of evidence about cycle helmets; short term, small scale, rated low for reliability on international scales of reliability, and long term, large scale, rated much more reliable on the same scales. The first shows massive benefits, while the second shows either no benefit or an increase in risk with helmet wearing. The media endlessly report the first and ignore the second, leading most people to believe that helmets are effective.

You might be interested in my MSc Dissertation on the subject of cycle helmets “Do cyclists have an exaggerated perception of the effectiveness of cycle helmets and the risks of cycling?” http://www.fietsberaad.nl/index.cfm?lang=en&repository=Do+cyclists+have+an+exaggerated++perception+of+the+effectiveness+of++cycle+helmets+and+the+risks+of+cycling

Well my helmet does not hold me back, it just protects my head.

Yeah I require my 8 year old daughter to wear one but the rest of us don’t. When we go on family bike rides my 13 year old daughter isn’t wearing a helmet, my 15 year old daughter isn’t, I’m not, and neither is my husband but my 8 year old daughter is. I told both of them that when they turned 13 that don’t have to wear helmets. My husband and I had really long debates about this, and I said they don’t need one. He is a Doctor so he thinks that they should but they don’t. So that my opinion

Good for you! I wear a helmet because it’s mandatory where I live, and I don’t want to be hassled by people “why aren’t you wearing a helmet”? But I’m tempted now…

LOL I just don’t wear one but my kids do I’m one of those silly moms that have their kids where one but i don’t sorry

Tis human nature to want to explain the inexpiable!

Tis human nature to want to ease suffering!

This is why we have helmet laws.

Why do we have helmet laws as opposed to improved infrastructure, easy: Which costs less?

For years the idea of bicycles and infrastructure was about as foreign as the idea that we could have two unacceptable political candidates as we currently have to choose our next president from. Figure that one out, and you’ll likely figure the other out as well.

Helmets on the other hand were a potentially profitable, private sector solution, to an occasional public tragedy.

And yes, speed kills, nothing new about that….the difference between a collision at 5 mph and 10 mph increases injury as does a collision at 15 verses 20mph. Do we really even have to contemplate the difference in injury severity and frequency between 20 verses 5mph? Why is this a surprise to anyone? Why do we spend money to study this, does anyone really question it?

I am an FBC (Full Body Cyclist) and ride at speeds of upwards of 18 to 25 mph near daily, for extended periods of time.

I also on occasionally ride a “road bike” and I will be riding at speeds upwards of only slightly less, but for shorter distances.

I wear a helmet, which is uncomfortable, like most I try on. It also leaves my locks (hair) looking rather ugly (sorry ladies some guys care what they look like too). Honestly, as I attend bike shows, and go in and out of bike shops, I’ve tried on a lot of very cool looking helmets, but none seem to “fit” my head configuration. Perhaps its because I’m from another planet?

At 18 years of age (I’m in my 50’s now) I was involved in a car accident. Not the cause of it, just an unwilling and unwitting participant. Just so you should not think I have some sort of phobia on the road, I am now, and was then also a Class A CDL TT driver, and Former Auto Racing instructor.

Anyway….I was on my way home at 11:pm at night, driving a relatively new Volvo station wgn. I was awaiting a left hand turn from the right side lane, when we heard this horrific sound, and then my windshield went red with blood. It was a second or two until we realized this, but even at 11:pm we somehow quickly deducted it was blood, and this wasn’t a good thing.

Some dumbass motorcyclist (I also raced motocross so I won’t apologize for calling a motorcyclists a name) with only a WWII helmet (with a spike) on, was riding the yellow line in the oncoming direction. He was riding an old Triumph that he’d “chopped and raked” for those unsure of what this means, think Steve McQueen and American Cowboy. The idiot had lots of chrome on the bike, but not a single headlight. So he did not see me, nor did I see him, and thankfully I was sitting still waiting to make a left turn. The motorcyclist still managed to rip his leg off his body on my front left fender/direction signal. Suddenly he could no longer work at his job as a machinist, and somehow that was my fault?

He lived, but for three years following, I was under pressure as his claims went through the legal process. At the end of the day…they said, (medical and first responders), that even though it wasn’t strapped on his empty head, the helmet saved his life. Go figure. So, I really think, often, long and hard about this helmet matter.

I was also a serious skier, and did a lot of “free style” skiing. In competition we were required to wear helmets. They limited our view, often times hurt our neck or shoulders, but undoubtedly saved our lives. (You’ve never imagined why a helmet is needed on a ski slope until you see the broken ski embedded in the helmet worn by team mates who collided in a cross jump flip during a free style event.)

Helmets may not save all that many lives, I’ll easily give you that…but as they saying goes, even if it only saves one….isn’t that worth it? Before you answer, imagine its the life of your loved one?

That said, I do not like helmets, nor are they for even a second to be considered a fix or even partial solution to these much larger problems of keeping bicyclist, skiers, football players and so on, alive and healthy. Any why isn’t someone developing a helmet that doesn’t play havoc with visibility, neck injury or even hair styling? There is the need, the profit motive should be enough….someone, fix these issues. But people don’t want to pay more ($10 on average) for the simple MIPS improvements to helmets. How will you get them to even wear one, let alone pay for it? Education, and progress.

And we all know well enough no one wants to foot the tab for expanded bicycle infrastructure! But it has to be.

Until recently I lived in a wealthy suburb where we were fortunate to have the ECG (East Coast Greenway) come right through the center of town. You would not believe the outcry from the NIMBY crowd! They “studies” they showed and quoted, invasion of private property, lewd acts taking place adjacent to the rail-trail, crime of all sorts. People sued to prevent the trail from coming through, others extorted monies for fencing and plantings of barriers to protect their own property. It was really rather entertaining to watch in the following years as the fences had gates cut into them, or shrubbery was removed so folks could access the trail. It was really sort of bittersweet to observe as properties adjacent to the rail trail appreciated 10% to 15% more than those right across the road without direct access. Suddenly, everyone wanted to be by the rail trail.

We need more infrastructure that puts a barrier between vehicular traffic and HPV traffic (Human Powered Vehicles). We need this so we can encourage people to get on bikes, become active and reduce the nations healthcare costs and increasing productivity including people getting out and living their lives.

The only way to do that is to defy human behavior, which is to overcome the fear of speaking out and advocating for paying for these infrastructure changes. We need to put space between vehicle and non-motor vehicle traffic. We need to implement a serious educational program at most levels, the medical community to the first graders learning not just to ride a bike, but how to ride a bike. We need to stop the fear mongering about disc brakes that cut people in half, and helmets that result in injuries worse than ones with no helmet.

Mostly we need to modify human behavior and stop talking and start taking actions to move these issues forward.

I liked the comparison to needing a helmet for other day-to-day activities. Heaven knows I’ve had more near-misses as a pedestrian than I can count. They’ve always been caused by inattentive drivers, and I would not likely have been helped if I had been wearing a helmet in those situations (call me crazy, but I think having your torso crushed by a bus would negate any benefit a helmet could give you).

I may be moving to Australia in the near future, and I have to admit the knowledge that they mandate helmets for everyone is disheartening (where I live now, only minors are legally required to wear them). There’s nothing like riding down a quiet street or path, with the wind in your hair, enjoying the freedom of a nice bike ride.

Thank you for share this informative article. Waiting for next article as i am a regular reader of this blog.

A driving factor behind some of the confusion is that many nontechnical authors conflate population level effects with individual level effects. What may true on average in a population, does not necessarily hold true an individual basis. For example, many researchers question whether mandated use will make a population as a whole safer due to auxiliary issues that occur in tandem (e.g., reduced total ridership), this population level effect does not mean a helmet will not help an individual in a crash situation.

Estimating exactly how much a helmet will help is difficult because you cannot randomly assign helmet usages and crash scenarios to people then measure the outcome. As a result, you are left depending on “natural” experiments, where people self-select themselves into treatment groups. This can lead to problems of “sampling bias” which was pointed out by Dr. Robinson. The existence of sampling bias does is not evidence against the effectiveness of helmets (as implied by the author), its only that the effect estimate may not be representative of the population of interest (or that population the statistic applies to – e.g., risky cyclists who wear helmets – is not the population you set out to measure – all people who may ride a bike ). In terms of the Thompson study (the 89% effect size), it is true the helmeted cyclists could on average be taking more risks and crashing more often, what is not pointed out is that this could also mean a higher baseline risk for head injuries and therefore the estimate of helmet effectiveness may also be an **underestimate** of the true effectiveness, if we could some how control for the severity and frequency of crashes. This is the problem with self-selection sampling bias, it is not clear exactly what is being measured.

Confounding the issue of whether or not a helmet is effective to an individual in a crash, we are mixing in behavioural changes (i.e., individuals without a helmet ride in a safer manner). This is important consideration when looking at population averages (i.e., do helmets make the population safer on average), but is misleading if the question of interest is whether or not a helmet will help an individual in a crash (what most individual readers will be asking). Unfortunately, many authors try and conflate these two separate issues.

As a counter example, we know from clinical psychology that if we place a giant spike on the steering column of cars people will drive more safely and be involved in fewer accidents due to the change in risk profile. Does this mean we should advocate for spikes on steering columns? Perhaps…

The underlying fact is we are constantly computing risk profiles in our head. When cars became “safer” with abs brakes and airbags people adjusted their driving habits so that their total risk tolerance did not change. In a similar manner communities that have better cycling infrastructure the probability of a crash is lower, therefore the risk of head injury is lower and people adjust their behaviour by not wearing helmets (e.g., the first article figure showing helmet usage rates and head injury). This does not mean going without a helmet magically reduced their risk of head injury. Correlation really does not imply causation (otherwise shark fatalities are truly driven by ice cream sales – google it).

None of the above nuances as any direct impact on whether or not a helmet will reduce your chances of a head injury if involved in a crash. To imply otherwise is misleading, and does a disservice to the readership.

So what do helmets do anyway? The do not “absorb” impacts as is often misstated (the article stated it “cushioned” which is also misleading). They do not dissipate force, but extend the time of impact by about 6 milliseconds (the time it takes for the foam to compact down). While 6ms may seem silly, it is crucial. In a crash (with or without a helmet) no matter what your brain has to dissipate the same total energy. Your brain can deal with some blunt force impacts, by extending the time impact time by 6 ms you substantially decrease the peak force, from something that could kill you or cause severe injuries down to something more survivable and/or less severe injuries. Other sports helmets such as hockey and football do not typically use crushable foam as it is one use only.

Now one way bicycle helmets still need to improve is dealing with rotational injuries. Impacts are not only linear (i.e., straight on), many are also glancing. Concussions are often linked to rotational injuries caused by glancing blows. Helmets that are hard shelled and smooth (i.e., slippery) go a long way here, there are also a number of newer technologies that try and introduce additional slip-planes to dissipate rotational forces. Slip planes may also reduce the rates of neck injuries as it introduces more play into the system. The effectiveness of these is still up for debate because of the difficultly of measuring effectiveness in real world situations. Difficultly in measuring does not mean there is a lack of an effect. Much of the difficult revolves around the simple fact we don’t condone (and rightly so) direct testing on people (e.g., “Ok Joey, we are not going to give you helmet and we are going to make you crash over your handle bars – repeatedly – and see how often you crack your skull or get a concussion).

**TAKE HOME**

These types of articles really need to separate issues facing the individuals versus issues facing a society. While there are good arguments NOT to mandate helmet laws, this does not mean helmets are not effective for an individual. You really need to assess your riding conditions, behaviour and likelihood of a crash. No one ever plans for a crash.

That’s a lot of words, none of which change this basic fact: when a large population increases its rate of helmet wearing, such as when Australia passed its helmet law, there is no measurable positive safety effect. There are many other things that do have measurable, positive safety effects. Why not focus on those and drop the helmet nonsense?

“we know from clinical psychology that if we place a giant spike on the steering column of cars people will drive more safely and be involved in fewer accidents due to the change in risk profile.”

We don’t know this. This is just an idea that seems self-evidently true, like the idea that helmets are useful. But no one has done this experiment, so we don’t know. What we do know, because these experiments have been done, is that placing cameras and other monitoring equipment in a car will make the driver extra well-behaved, but only for a few days. After that people get used to the situation and revert to unsafe driving. We do know, because the experiments have been done, that people will strive to “get ahead,” limited only by their fear of personal consequences (physical, moral, legal, etc). This is why the only reliable safety program is road design that, for example, forces drivers to slow down where people are present or that physically separates traffic to reduce vehicle-vehicle crashes.

My point is that we may all have nice ideas, but we are humans an humans are flawed. We need to rely on real-world data. People do not ride bicycles in emergency rooms, they ride them in cities, suburbs and rural areas. Thus, the useful information comes from city-level or regional population studies, not studies that are limited to the subset of the risk-taking, unhealthy, or just plain unlucky people who find themselves in emergency rooms.

“That’s a lot of words, none of which change this basic fact: when a large population increases its rate of helmet wearing, such as when Australia passed its helmet law, there is no measurable positive safety effect.”

A couple of points about the before/after Australian helmet law studies (and there are multiple studies on the subject):

(1) Lack of an estimated effect is _not_ evidence for a lack of an effect. Lack of statistical power, sampling bias, lurking and confounding factors are all things can obfuscate an effect making it hard to detect. Studies on Australia’s helmet laws have found evidence for and against, yet many seem to cherry pick the results that are against (better click bait material I suspect).

(2) Real world data is messy. It is not a controlled experiment, there are a lot of other confounding and potentially lurking factors occurring at the same time in these before/after designs. For example time is inextricably confounded with the effect of interest. This is why in environmental research these types of designs are thrown out as being insufficient, with a Before/After-Control/Impact (BACI) being the minimum level of quality. The control site is used to assess potential time effects. None of these helmet studies even have controls. The evidence is very tenuous.

(3) Lack of an observed population effect does not mean they do not help the individual. You cannot always apply population level effects to individuals (called an ecological fallacy), otherwise putting glasses on would make a person smarter. (Studies have shown people with glasses rate higher in intelligence measures).

I think many of you are trying to misapply the research in favour of your political ideologies. I am personally in favour of more cycling infrastructures over helmet laws, but to imply that helmets have no beneficial effect for an individual is misleading at best.

Rider X, Thanks for the sharp critique of this post. I agree that this article mixes too many variables and makes too many inappropriate comparisons: who in their right mind would use their head as a weapon, particularly while riding a bicycle?

As a lifelong cyclist (58 of my 64 years), an LAB League Cycling Instructor (#3175), and a user of hardshell styrofoam helmets since 1975, I can personally attest to their efficacy in protecting against severe brain injury. I have survived three (3) major head-impact collisions thanks to wearing helmets on a regular basis. My neurologist agreed, saying I had probably saved tens of thousands of dollars in brain surgery by wearing them when: a) hitting a quarter-sized oil patch while making a legal U-turn at a signalized intersection, b) hitting an unavoidable road hazard at speed while being passed by a speeding car, and c) sliding out on wet steel railroad tracks that the street configuration made it impossible to cross at right angles. In all three cases I went down instantaneously and hard, hitting my head. (I have been treated for epilepsy since the age of 8, but only road hazards or autos–never seizures–have caused collisions.)

I liken bike helmet in the United States, where roadways and drivers are far less bike-friendly than they are in Europe, to buckling my seat belt whenever I am in a car. Driving–like cycling– is a relatively safe activity most of the time, but wearing a seatbelt prevents serious head injuries in the event of a collision.

It may be that some day–probably after I leave this life, although I have been working since 1971 for that day to arrive far more quickly–our roadways and streets will be both safer for people (pedestrians, transit users, and cyclists of all ages) and filled with far more bicycles than they are today. Perhaps then our streets might be risk-free enough to make cycling without a helmet a rational choice.

But until that day comes, simple prudence and common sense tell me it is smarter to wear a helmet whenever I ride than to go without one, just like wearing a seat belt is smart every time I am in a car. It is only wishful thinking to believe that going helmetless is the “politically correct” way to make our streets safer than they really are

You may be a bicycle instructor but Charles Tator is a leading neurosurgeon at Toronto Western hospital, (Canada’s preeminent brain trauma center) as well as a professor of neurosurgery at the University of Toronto again a top med school and his opinion on the efficacy of bicycle “helmets” Styrofoam hats would be a more accurate name for them (my words not Dr Tator’s) stands in direct contrast to yours. If you don’t understand rotational brain injuries, also called diffuse axonal injuries you do not understand the dynamics of brain injury and bike helmets in no way what so ever protect against rotational forces and in some cases can magnify them by increasing the diameter of one’s head adding additional torque to an impact. Anyhoo here’s an article about the efficacy of bicycle helmets vis-à-vis brain injury with some quotes from Dr Tator as well as another brain trauma researcher.

http://www.cbc.ca/news/health/bike-helmets-should-address-concussion-risk-scientists-say-1.1367454

There is plenty of additional research that supports his claims, if interested I will post.

“This helmet thing is a huge, huge diversion of very smart people’s time and energy.”

Thanks very much for this article. I have talked to several people over the years who have been discouraged from cycling because of helmet laws or helmet promotion. Some just plain don’t like helmets. Some want to cycle to do everyday errands and see the helmet as one more thing to juggle along with children or groceries.

The fact is that small things matter. Discouraging messages matter. The very fact the the “helmet wars” exist leads people say “if the bicycle people can’t agree on what’s safe, I’ll spend time where people seem to have a clue about safety.”

When I wear a helmet I feel like I’m part of the problem, not the solution. As a result, I am motivated to avoid rides, events, and places where bicycle helmets are required. Unfortunately this includes most government facilities in the USA. Since I work for the government and have family in the military I often have to pack a helmet.

Your article on bicycle helmets is irresponsible. Ask any pediatric emergency doctor about the impact of helmets in saving lives and preventing significant head injury and they can provide any number of real life accounts of what a helmet can and can’t do to protect the vulnerable brains of our community’s children.

From a personal standpoint, outside of my role here in pediatric public health, I can say that a bicycle helmet saved my son’s life when he was five. He flipped over his handlebars while riding in our neighborhood after he slipped on some gravel less than a quarter mile from our home. Had he not been wearing a quality helmet, which split open when he hit the ground head first, he would have had at best a major head injury and skull fracture but likely would not have survived the trauma. As it was, even with a helmet he had a broken nose, facial abrasions, concussion and major bruising under the helmet. But the helmet bore the brunt of the impact.

Instead of lamenting that bicycle helmets prevent people using bicycles perhaps we should look instead to seat belts – people didn’t stop driving when they had to use seat belts. The law required it and our infrastructure changed to support it. The problem with lack of bicycle riding in the US is lack of good infrastructure and built environment, combined with a lack of policy around bicycle helmet use.

We work hard to prevent pediatric death and disability. One article like the one below can undo that hard work and put many children at risk.

You’re a doctor so I assume you have a strong science background. And yet you seem to be ignoring the adage that anecdote does not = data. Anyway, I don’t think this is saying that helmets are a *problem*, but that focusing primarily on helmets is a red herring in the bike safety conversation.

I have an anecdote for you. A well know bike advocate was killed by a drunk driver where I live a few years ago. He was wearing a helmet. Turns out they aren’t so useful when an urban street is designed so that a driver can hit 50mph.

I think we need more people in the medical research community like you involved in this discussion. We share a common goal of reducing head injuries in bicyclists, but have different ideas about how to get there.

The fact that head injuries have been increasing while helmet use has been going up needs to be examined and explained by medical researchers. This study in New Zealand points out the risk of bicyclist injury from non-motor vehicle collisions (similar to your son’s collision) quadrupled in that country – after a precipitous rise in helmet usage: http://www.cycle-helmets.com/new-zealand-road-users.html. This points to the theory that people are more comfortable taking risks while riding a bicycle with a helmet.

It is doctors pushing these fake safety “helmets” that are being irresponsible. They are not taking any responsibility for the damage that they cause by scaring people of cycling. Less cycling, less exercise, less health benefits.

These doctors often fail to consider that wearing a “helmet” increases risk taking & increases the risk of accident. They are blinded by their belief that helmets offer “protection”. If they had bothered to inspect a bicycle “helmet”, they would have realised it is little more than a piece of polystyrene. It is naive to believe that a piece of polystyrene can provide significant “protection” in a serious accident.

It is irresponsible to promote bicycle “helmets” as the solution to cycling safety when they increase accidents while being too flimsy to provide significant protection. It is no wonder that bicycle helmets are associated with increased injuries.

Wake up doctors!

Instead of labelling others “irresponsible”, have a open-minded sanity check at the unintended consequence of what you are advocating.

By the way, a cracked helmet is a helmet that has failed to worked as intended.

http://crag.asn.au/the-fallacy-of-the-cracked-helmet/

As someone interested in the health of young people, which is the biggest threat to their health, obesity caused by lack of exercise, or injuries from playing, including cycling? Given that cycle helmets have killed children, and there is no proven case of a helmet saving a life, and that we are suffering an obesity crisis which will shorten millions of lives, the answer is clear.

Regular cyclists, those most exposed to the risk, live on average two years longer and suffer less from all forms of illness, so how can something likely to make you live significantly longer be dangerous? As one medical researcher said “If the benefits of cycling could be bottled, it would be the most popular medicine in the world.”

The myth of helmet effectiveness is just that, a myth based on bad science which has been disproved many times, but is still parotted by helmet zealots who refuse to even look at the evidence.

Yes, in the event of a serious collision a helmet may save your life. But the benefits far outweigh the risk! Cycling without a helmet is more convenient, might make you ride safer, and it encourages more people to bike! And when more people bike, drivers become more aware and the danger is far reduced!

The likelihood of a serious collision is low enough that it shouldn’t even be considered. I’m not scared to fly on a plane, why should I be concerned about riding my bike? Driving is actually far more dangerous than we realize. I’m certain that in my life I will experience a nasty car crash.

I don’t have to pay for gas, insurance, or fares, and I’m not putting damage on the roads with a 2-ton cage.

I would still ride my bike even if it was unsafe, because the exercise and the freedom keeps me healthy and I feel great!

If helmets aren’t required, then more people bike. And when more people bike, it helps the city and more people enjoy the above benefits!

If there’s one thing I want, it’s healthy, happy cities. Cycling is a big part of that, so the fewer helmets, the better!

I was one of the slim minoroty for whom a helmet saved my life as I know it. I tend to ride town to town even as a commuter and so anything so minor as a helmet or a patch kit that will lend aid when I’m between destinations is still a sound investment. Here in Chemung Co. NY it’s not that we’re spending too much on the fear factor but tht we have active opposition from highway commisioners who see cycling as an unwantwd burdon on the motoring resource. Or the zero enforcment of existing bicycle traffic law, not just helmets but stopping people riding sidewalks agaist traffic with no loghts in the dark who then get hurt.

While I have no doubt you feel your helmet has saved your life Malachi, I’m a bit more sceptical because real life research has yet to bear out this type of claim in fact.

There are many points that go unheeded in such claims such as helmets can break at sub-lethal levels or that helmets work via compression rather than splitting. Also, while it is true about three quarters of deaths to those riding bicycles are attributed to head injuries, it is also true that in the vast majority of those deaths (around 75-80%) there are other injuries in these deaths that have led to death. Deaths from head injury alone usually make up less than 20% of all deaths to cyclists. Most head impacts cyclists suffer are to the face and side regions of the head to which a helmet can offer no protection. Reports also show most cycling fatalities are the result of impacts with motor vehicles (which the helmet manufacturers tell us bicycle helmets cannot provide protection against) at speeds in excess of the maximum impact speeds at which bicycle helmets are tested at and fail when exceeded.

There’s little doubt a helmet can help prevent some injuries in some situations, but to spread the idea that a helmet can do more than it is deigned to, or in situations it was never meant to be of benefit, is dangerous

Are helmets holding us back? Why, yes!

Helmet promotion is promoting the (false) idea that riding a bicycle is risky, and that’s not the way to get people interested in riding bicycles.

Brad, The United States’ streets and roadways ARE more risky than similar roadways in more bike-friendly nations (Denmark, The Netherlands, Great Britain, Germany, etc.), for a variety of reasons: 1) street and roadway design priorities (cars first), 2) vehicle codes and priorities (cars first, again), 3) law enforcement priorities and unfair enforcement (ditto), 4) the lack of driver training, education, and skill, and 4) the lack of proper education and training of cyclists, who usually treat bicycles as a toy or feel they are “outlaws” on our streets and roads.

On the basis of miles traveled, cycling is more hazardous than driving and injuries to cyclists are far more likely than injuries to a car driver in the event of a crash. (The football helmet analogy used in the post is far more applicable to car drivers in their lethal weapons than it is to comparing helmet-using cyclists to those not wearing helmets.) As other commenters noted, pedestrians are also at far higher risk than need be due to many conscious decisions made in the planning, design, construction, and maintenance of our transportation infrastructure.

The current levels of injury and death (tens of thousands of fatalities per year) are deemed “acceptable” but could easily be reduced. But until we adopt and implement “Vision Zero” priorities nationally for all of our transportation modes and infrastructure, the risk of death and injury from motor vehicle collisions will remain unacceptably high.

In the interim, it is unwise at best, if not downright foolish, to understate the risks of our current transportation infrastructure, laws, enforcement priorities, and attitudes to all roadway users–especially to relatively unprotected cyclists, who will almost always lose in a collision/contest of physics with a motor vehicle.

You are clearly fear mongering, there are absolutely not “tens of thousands” of cyclist deaths per year on US roads. When that horrible act of homicide occurred in Kalamazoo Mi and 5 cyclists died earlier this year an NTSB spokesman was quoted in the national media as saying there were 742 (I think from memory, seven hundred and forty something in any case) cycling deaths in the entire USA in either 2015, or 2014 whichever year is the latest for verified NTSB gathered statistics, often they are a year behind. Approximately 750 is in line with statistics Canada’s average of ~ 100 cycling deaths per year in this country.

As for the relative safety of bicycling v car travel v pedestrian travel you are again incorrect, depending on which country you look at they have relatively the same risk of causing a head injury. Walking on stairs or taking a shower are both significantly more dangerous than cycling. In terms of absolute numbers averaging across the developed world 6-10 times the number of pedestrian and 30-50 times the number of car travelers die of head injuries per year as do cyclists. Sadly in the first 6 months of 2016 here in Toronto 2 cyclist have died, one hit by a fast moving train (not sure about helmet usage) and one elderly gentleman (71 years old) who was wearing a helmet was squeezed into the back of a parked van by a car driver at approximately 30kph (20mph) in city traffic. In that same period 44 pedestrians, mostly hit by cars have died in the same jurisdiction. One UK study puts the risk of cycling at one death per 3,000,000 kms cycled, the graph above shows the risk as 100/1Billion km cycled for the USA, 50/1B in the UK and around 20/1B for France, German and Holland and even less for Denmark. That’s a very very low risk in all cases but even more interesting the risk is approximately 300/1B kms for Australia the country along with NZ that has the highest proportion of helmeted cyclist.

Yes North American roads are less safe then northern Europe in general but the differences are not that great and most of NA is improving rapidly with truly effective measures like vulnerable road user laws, better infrastructure and larger number taking up cycling fear mongering not withstanding. On the other hand whole population studies in Australia and New Zealand which now have the least safe roads for cyclists in the developed world sow a small but significant increase in head, and other injuries when helmet wearing rates more than doubled after they introduced mandatory helmet laws. The reasons are complicated while usage rates more than doubled overall ridership dropped ~40% leaving the remaining cyclists more vulnerable but another major factor is that bicycle helmets provide no where near as much protection (they do provide nominal skull and scalp protection and virtually no brain protection) as most wearers and proponents believe they do. Legislating, scaring or shaming people into wearing helmets is something unique to Anglo-centric societies and has very negative consequences for bicycle safety overall.

Should have added these pages for reference.

http://www.vehicularcyclist.com/fatals.html

http://www.vehicularcyclist.com/kunich.html

I’m sure you’d consider this web site biased but the data comes from government statistical gathering agencies like Transport Canada, the U.S. Department of Transportation, the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration and others cited in each piece. Prove to me that they are incorrect.

Should let this slide but it’s not in my nature to allow pernicious attitudes about bicycle safety to go unchallenged. I was killing time on the NPR Car Talk web site and felt this post backed up by data from the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration clearly shows the relative risk of death between Cycling, Walking and traveling in an automobile, namely that the each carry relatively the same degree of risk so either wear a helmet to all or quite shaming people who chose not to wear a helmet for any.

http://bestride.com/news/safety-and-recalls/bicycle-vehicle-accident-deaths-show-unexpected-trend

i wear a helmet”because i have to” BUT not once has it got into my head that because i wear one i can be more reckless,unlike motorists sitting in their steel }helmet” and airbags they can be totally reckless especially around cyclists.

Then you are one out of probably a billion people who can control their sub-conscious mind at will.

Agreed. Completely. The misguided focus on Helmets = Safety detracts from more important safety issues. Here’s my take on it: http://www.cantitoeroad.com/Dumbos-Magic-Feather–The-case-against-bicycle-helmets_b_19.html

I fell while dismounting….backwards….hitting my head on the pavement….I was wearing a helmet….no problem…no question, the helmet helped….why is it a problem to put a helmet on?….

Statistically, the fact that *you* fell and hit your head while dismounting from a bicycle has no bearing on whether a helmet is relevant to bicycle safety. The article isn’t saying that it’s a *problem* to wear a helmet while bicycling, but that it’s a red herring. Helmet-wearing is not going to lead to greater safety for the majority of bicyclists. It’s an anomaly what happened to you. What will help cyclists exponentially more than helmets is dedicated cycling lanes, more people cycling, less people driving, slower traffic, a culture that prioritizes health and happiness over speed.

Great comment? Are you the One Cyclist In Lisbon?

Thank you for writing this! Can you get one of the major papers to do a story on this?

It is none of your business how I dress.

A helmet would prevent me from wearing the head coverings I prefer. It was chilly for June today so I donned a béret. I don’t cycle when there is a lot of snow or ice but I cycle in weather cold enough to need a tuque.

While I usually work at home, sometimes I have to be presentable at work (conferences etc). I take it that you are a dude, and will call women “vain” if we don’t want to show up to work with filthy, sweaty matted hair – but sack us if we do show up looking like a vagrant.

The cure for that nonsense is a trip to a cycling-friendly country.

My sentiments exactly. Showing up to work with sweaty, matted hair would be considered unprofessional enough that it would cause issues in most work environments, and if you have long hair it’s not exactly an easy fix once you’re at work. Talk about discouraging bike use. Thankfully I live in a province that only mandates helmets for minors, and not adults, but I will agree that helmets discourage riding for many people, and are much less important than proper infrastructure and motorists being used to cyclists.

Happy to see Momentum Magazine continuing to examine this issue. There was one article published some time back saying they were going to put it to rest, so this submission gives me hope.

I view helmet promotion to be anti-cycling promotion with the ultimate blow to people riding bicycles being mandatory helmet laws. These laws forbid people to ride bicycles unless they wear helmets and I believe that is bad not just for those riders who do not want to wear helmets, but for everybody.

I’m curious. You interviewed the Thompson’s, and obtained the quote about cycling helmets being an “easy” solution (or not a solution at all IMO). But what else did you obtain from that interview? It doesn’t appear to inform any other aspect. What were there views on their study being discredited?

Hi Wryguy,

Before I interviewed the Thompson’s, I had some preconceived ideas that they were kind of like the enemy, mainly because I believed their study was so damaging (especially after reading the criticism of Dorothy Robinson). But they were very kind and generous people who have done a lot to contribute to the field of epidemiology, working to reduce colon cancer, domestic violence, and smoking (probably among other things). They sent me a paper copy of their study after I told them I couldn’t find it online without having to pay an exorbitant fee – very nice people! I also realized as I was talking with them that they were retired and at the end of long, successful careers. And then they reminded me of so many people in that generation who had their careers when bicycling was not as popular (in the ’80s and ’90s), and road racing/training was coming into vogue. So I ratcheted back my criticism toward them, and became much more respectful of their position. They are aware that there is opposition to helmets (I asked them what they thought of it). Their response was pretty simplistic, and they were defensive regarding the possibility that their numbers were inflated. I chose not to press them on these criticisms, but I’m assuming they may want to respond if they read this article. They did a couple of follow-up studies in the ’90s (which they also sent me), with somewhat similar results (although not as strong). As I was writing this article, I realized how much things have evolved since they started their research 27 years ago. I think they are good people who have very good intentions. I disagree with their position obviously, but I believe that sometimes our opposition deserves more respect than we feel like giving at the outset. One more thing, I was careful to say that their study was “outdated” and not “discredited”, because the nature of research is that it constantly evolves. Another researcher I interviewed reminded me of this distinction. Thanks for your question Wryguy, it is a good one.

Did you ask them how much undeclared funding they accepted from Bell bicycle helmets?

I read details which indicate that the rates of head injury in crashes is substantially higher for those inside a car, which prompts many to suggest that rather than focus on cyclists, or attention should move to those inside cars who should be wearing helmets instead.

Personal experience in a number of crashes has included some where had I been wearing a helmet I would be dead or very badly injured, not having an enlarged head ensured that it did not touch the road and snatch my neck, the time I watched the white line passing inches below as I cartwheeled down the road, having just written off the car which had been driven into me. It has enabled me to ‘go foetal’ with the head and neck intuitively tucked in to the chest and arms closed over them to roll down the road after flying over the ‘bars at around 30mph.

Research from the late 1940’s also highlights that 2.3bn years of development has already delivered brain protection which is only at 30% of its capacity to absorb a ‘flat’ impact at 20mph, whilst the styrene lids designed for a 12mph impact are well past their destruction point (260%) at 20mph. The cranium with its clever fused multi-plate structure is actually a very neat way to protect the brain, and its self-repairing covering, which shears rather than snatches in any oblique impact (albeit in a very bloody way) prevents the biggest danger, which many designs of helmet may enhance, the severe rotational acceleration of the brain, as it ‘floats’ inside the skull, rupturing key connections.

Finally you only have to return to the most fundamental hierarchy of safety, which places Personal Protective Equipment right at the bottom of the interventions, beginning with the most basic one of removing the hazard. Put simply if your only safety intervention is to make people wear PPE than you have failed nem con.

Excellent article! I have one serious complaint, though. After reading it, one is left with the idea that to achieve even more bike safety, the choice is between the discredited helmets and segregating bikes from cars: “we should be arguing for bike paths, protected bike lanes, and traffic calming – not focusing on the bicycle helmet.”

In North America, we will never be able to segregate bikes on a significant portion of our streets and roads. Bike riders will always have to interface with traffic. And even when “protected” bike lanes and bike paths are built, riders must still deal with drivers at every intersection and every driveway crossing. Those are precisely where most car-bike crashes happen, and these bike lanes and paths usually complicate the crossing traffic interactions.

There are better solutions. Educate kids and adults on how to ride on normal streets and roads, because there is much to learn. Train motorists on how to interact with bikes. Most importantly, publicize and enforce the idea that bike riders do have full rights to the road. Education is far better than pipe dreams about paths everywhere.

“In North America, we will never be able to segregate bikes on a significant portion of our streets and roads.”

I reject the idea the we in the USA are a bunch of losers who are incapable of doing great things. Of course we can build cycling infrastructure that works for real people. As more people ride (and as our great cities become more dependent on transit, which goes hand-in-hand with biking and walking), citizens will demand safer biking (and walking).

The United States has roughly 4,000,000 miles of streets and roads. So far it’s got roughly 200 miles of “protected” (except at intersections!) cycle tracks. That’s 0.005%. I don’t see that growing to any significant number within our lifetimes.

For the other 99.995% or streets and roads, AND for the intersections where cycle track “protection” turns into extra danger, education is still needed.

Education works right now. Why aren’t we giving 99+% of our attention to education, instead of to segregation fantasies?

A published analysis of American cycling participation trends and injury rates is at http://www.cycle-helmets.com/us_helmets.html

The rest of the website makes clear that helmets are having a disastrous impact on public health and road safety in various countries.

Excellent article. The Australian experience very much lines up with this. It’s very frustrating when politicians choose to tow the party line or listen to one myopic medical group rather than examining the actual evidence (and listening to other medical groups). I hope the USA stays sensible on this issue and continues to reject helmet laws.

Comments are closed.