Just a decade ago, public bike share wouldn’t have caught even the half-hearted attention of most city planners. Its earliest incarnation – a program of free bicycles scattered around Amsterdam in the 1960s – relied on the honor system and as a result was ineffective and short-lived. After a few more unsuccessful attempts at free public bike share by a few cities and towns around the globe, it seemed the world was ready to give up on the idea altogether. The 2005 launch of Velo’v in Lyon, France changed the game. Velo’v introduced corporate sponsorship and information technology into the system, and in the process proved to the world that public bike share can be a viable and desirable addition to any city’s transit ecosystem. In the years since, hundreds of bike share systems have popped up all around the globe, from Helsinki to Hoboken.

But for all the enthusiasm and excitement around bike share, there are also concerns being raised over its impact on business. Like any bicycle infrastructure project, public bike share provokes the ire of business owners and associations who believe the installation of bike docks around their storefront will negatively impact their bottom line. While there isn’t a wealth of data on the business impact of bike share due to its relatively young history in the grand scheme of urban consumerism, from what we do know, things are looking good.

Who’s Parking?

One of the most common concerns voiced by business owners over the installation of bike lanes, bike parking, or a bike share station is that it will remove valuable parking spaces from their customers. If their customers can’t park their cars, as the reasoning goes, then they won’t be able to shop. And if they can’t shop, the business will inevitably suffer. As it turns out, this reasoning is based on two false assumptions: one, that the majority of customers are already arriving in cars, and two, that car parking is the most economically valuable form of transit-based customer acquisition.

A 2011 study by the Dublin Institute of Technology found that most merchants in busy commercial centers overestimated the number of their customers who arrive by car, and underestimated the numbers arriving by bike, on a bus, or on foot. Merchants on Grafton St and Henry St estimated that 13% and 19% of their customers arrived in cars, respectively, when in fact it was only 10% and 9% respectively. Merchants on Grafton St estimated that 4% of their customers were arriving by bike, when it was 9% on reality. Henry St merchants correctly guessed the disappointing cycling modal share of 3% for their street, which the study authors argued could be caused by a lack of cycling infrastructure in the area. In general, the most underestimated forms of travel were bus and walking, which together made up the wide majority of customers arriving to each street.

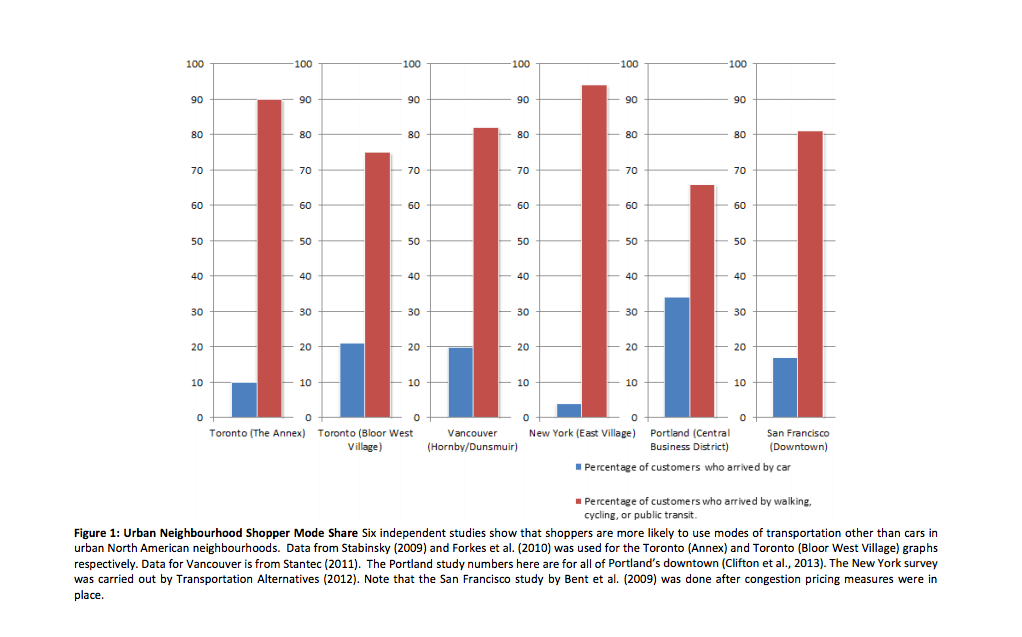

This research is corroborated by six other independent studies which looked at urban shopping mode share in five North American cities: Toronto, Vancouver, San Francisco, Portland, and New York. When the data was compiled by the Toronto Cycling Think & Do Tank, it became plainly obvious that cars are not the preferred mode for urban consumerism – walking, cycling, and public transit together make up the bulk of trips in each city. Since public bike share is an important element of the urban public transportation eco-system, it stands to reason that a business would gain customers from proximity to a bike share station.

Graphs from a Toronto Cycling report on the economic impacts of cycling.

But Who’s Buying?

“Okay, sure, more customers are arriving on bikes than we thought, but who wants cyclists as customers anyway?”

Once you’ve convinced business owners that sacrificing a parking spot for some bike racks or a bike share station will bring more customers in sheer volume, you’ll often hit a second roadblock. Many business owners don’t particularly care to cater to bike riding customers. They believe people who ride bikes do so because they can’t afford cars, and as such won’t be particularly valuable customers.

In fact, it’s quite the opposite.

A 2008 study undertaken by urban planning researcher Alison Lee compared the economic contributions of cyclists to drivers in Melbourne’s shopping strips. Lee found that drivers spend more than cyclists per hour, an average of $27 compared to $16.20. However, since 6 bikes can fit into a single car parking stall, the potential payout for that space is $97.20 per hour if converted to bike parking. Lee argued that there would be an economic gain to converting more car parking to bike parking. A separate study undertaken at the University of Portland in 2012 found that, although cyclists do indeed spend less per trip, they make more frequent trips, resulting in a higher average monthly spending than people in cars.

Researchers at the City University of New York undertook a study in 2013, analyzing the specific economic impacts of converting curb space from on-street car parking to public bike share docks. The authors examined reported usage patterns of 7 bike share stations in different New York City neighborhoods, which held a total of 283 bikes, generated an average combined total of 587.3 trips per day, and replaced 41 automobile parking stalls. By comparing the usage frequency of bike share docks to car parking stalls, and the average spending patterns of each user, the researchers estimated that the conversion of 20 feet of curb space to a bike share facility has the potential to increase commercial spending from $219.65 per day to $334.06 per day, an increase of $114.41.

So What Are We Waiting For?

Nothing, really. Public bike share has seen explosive growth worldwide in the past 10 years, and the momentum shows no signs of slowing. As of June 2014, there were public bike sharing systems in 50 countries across 5 continents, operating approximately 806,200 bicycles at 37,500 stations. While the naysayers will always remain, the evidence is speaking for itself at this point, and cities are listening. Now we just wait for the money to roll in.

Get your FREE copy of our new guide: Momentum Mag's E-Bike Guide

In this guide we explore some of the different ways an e-bike can provide solutions for different users, outline the different types of e-bikes available, give a briefer on the technological components, and offer some advice on purchasing your own electric bicycle.

Thank you for your submission. Please check your inbox to download the guide!

Bike share is the flavour of the month but I doubt current interest can be sustained in all the places where it has appeared recently. It makes the most sense in cities with lots of young tourists and some bike friendly infrastructure and also in cities with a large transient college & university student population. When the systems for renting a bike become easier to use (by waving a smart phone, for example) the idea will become more viable. Where I live, some bike share users are urban cyclists who own bikes but who use the share bikes when the weather is wet or dark (because the share bikes have fenders & lights) or when they need to carry shopping home on a rack or in a basket. The system we have here is all on the bike – the racks are just “dumb” lock up points and the bikes have built-in u-locks that can be used anywhere, not just in the dedicated racks.

Comments are closed.