The more people biking on a city’s streets, the safer each individual bicyclist becomes. Dubbed the “safety in numbers” phenomenon, this pattern was originally identified by researcher Peter Jacobsen back in 2003. Now the National Association of City Transportation Officials (NACTO) has run the numbers in 7 American cities to see how their initiatives to increase cycling have paid off both in ridership and individual safety, and their recent report confirms what Jacobsen had already found to be true.

Riders on Chicago’s Divvy bike share system.

NACTO undertook a survey of 7 cities, highlighting the policies and projects which have been successful at increasing ridership, including in low-income communities and communities of color. The resulting report, Equitable Bike Share Means Building Better Places for People to Ride, makes a clear case for the “safety in numbers” approach to bicycle planning, with bike share and bike infrastructure at the forefront of the effort.

“In cities that are building protected bike lane networks, cycling is increasing and the risk of injury or death is decreasing,” the report begins. “Pairing appropriately-scaled bike share with protected bike lanes increases ridership and is essential to equity and mobility efforts.”

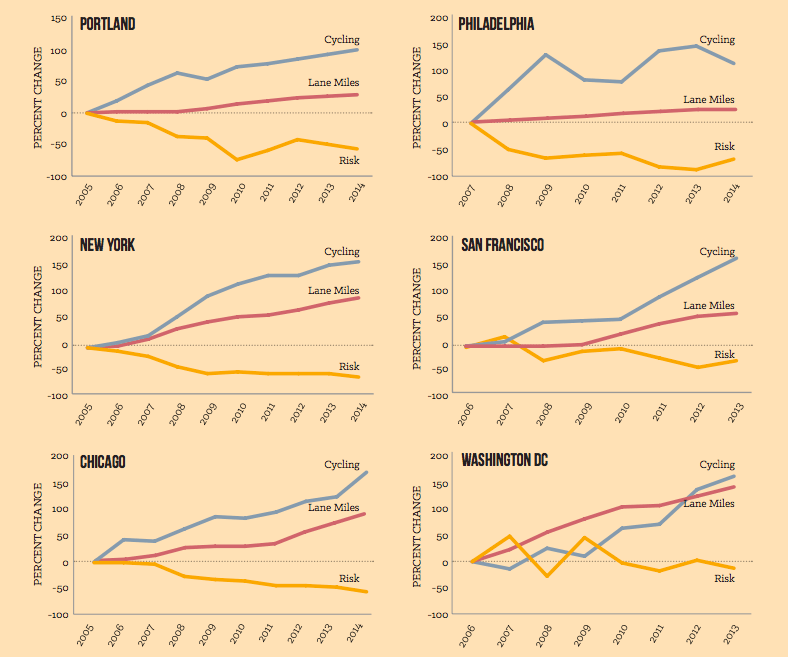

NACTO collected data on bike network mileage, number of cyclists killed or severely injured (KSI), and bicycle volume in Chicago, Minneapolis, New York City, Philadelphia, Portland, OR, San Francisco and Washington, D.C. In all seven cities studied, the risk of injury to each bicyclist declined as the volume of ridership grew. In five of the seven cities studied—Chicago, Minneapolis, New York, Philadelphia, and Portland—the absolute number of cyclists killed or severely injured declined between 2007 to 2014, even as cycling rates soared. And in the remaining two where the absolute injury number increased, its rate of growth was far outstripped by the rate of growth in cycling.

Each of the seven cities studied have made significant investments in safe cycling infrastructure over the past few years, specifically “high comfort” bike facilities such as protected bike lanes. Appropriately scaled and accessible bike share systems, when built in tandem with safe cycling infrastructure, can dramatically increase ridership and build political momentum for further investment in bike infrastructure, creating a virtuous cycle of increased and improved ridership. For example, over 10 million trips were taken on New York’s Citi Bike system in 2015, increasing both the volume and visibility of riders on New York’s streets.

The report also notes the incredible safety record of public bike share systems. Between 2010 and 2015, there were over 62 million trips taken on public bike share in the US, and zero fatalities. Numerous theories have been posited for the relative safety of cycling, but this latest report suggests much of it has to do with public bike share’s ability to increase bicyclist visibility on city streets by creating new users. “Put in simplest terms, a driver who sees 20 cyclists over the course of a few minutes is less likely to forget to look for cyclists than a driver who sees just one.”

The report notes that these investments are particularly crucial for low-income people and people of color, who make up an increasingly significant portion of the bicycling community, but suffer injury at much higher rates than their upper-income and white neighbors, due to a lack of safe cycling infrastructure in their neighborhoods. Building safe cycling networks that extend into low-income communities is essential to equity and mobility efforts.

The report stresses that safe cycling infrastructure, particularly All Ages and Abilities facilities such as protected bike lanes, are key to attracting new riders. Specifically, many bike share users are new riders who wouldn’t ride if it weren’t for the availability of safe bike lanes. “Concerns about safety and the lack of bike lanes are cited as a main reason not to ride among low-income people and people of color,” the report reads. “Protected bike lanes make cycling accessible to the majority of the population who have reason to ride but are concerned about safety, dramatically increasing the pool of people who might choose to use bike share.”

NACTO also examined the impact of mandatory helmet laws on ridership, synthesizing the available data to conclude that mandatory helmet laws reduce bike share ridership and don’t increase bicyclist safety. Moreover, mandatory helmet laws pose additional issues for low-income communities and communities of color. “Reports from around the United States suggest that such laws often give police an additional reason to stop and question people and are disproportionately enforced against low-income people and people of color,” the report reads.

The report concluded with seven key lessons drawn from the seven cities studies that could serve as a benchmark for other cities looking to successfully and equitably grow their bicycling communities, which are worth reproducing in full:

Support bike share systems with significant buildout of bike lanes networks: Ensuring that people have places to ride where they feel comfortable and safe is essential to larger equity and mobility efforts. The safety benefits of increased ridership are enhanced when growth in cycling is matched with construction of new, better bike lanes.

Design for the “Interested but Concerned:” The majority of the U.S. public is interested in biking but concerned about safety. Their willingness to ride is highly influence by the quality of bike lanes available to them. Matching convenient bike share systems with a protected bike lane network is a recipe for success.

Remember who is already riding: Half of the people who bike to work earn less than $25,000/year. Years of highway building, car-based zoning, and exclusionary housing policies means low-income neighborhoods are often separated from job centers by highways and dangerous streets with limited-to-no space for bikes or pedestrians. As cities build for more cyclists they should ensure that the bike lane network includes safe routes for existing riders.

Long term community engagement is essential: People in all neighborhoods want safe places to walk, bike, and play. Building long-term, reciprocal relationships in neighborhoods and with locallytrusted community organizations is essential to spreading information, getting feedback, and building local support for projects.

Use bike share stations as tools for safety: Bike share stations can be placed in ways that increase overall street safety. Planners should strategically place stations in ways that define and protect bike lanes and pedestrian space, narrow streets to reduce speeding, and create pedestrian refuge islands that shorten crossing distances.

Eliminate mandatory adult helmet laws which restrict and reduce cycling: Mandatory helmet laws reduce the number people riding and negatively impact overall cycling safety. In addition, such laws can be prone to abuse and are often disproportionately enforced in low-income neighborhoods and communities of color.

Counting counts: Measuring the growth in cycling is one of the best ways to tell if a city is working effectively to make cycling commonplace, easy, and safe for everyone. Cities should focus on the trend of cycling and cycling risk—is it increasing or decreasing and by how much—year over year to get a big picture view of the success of their bicycle program.

Get your FREE copy of our new guide: Momentum Mag's Urban Cycling Guide

In our latest free guide, we share a few tips and tricks for anyone new to urban cycling who is looking to get started. We discuss the latests numbers regarding safety and cycling as well as go over a few rules of the road that every cyclist should know.

Thank you for your submission. Your free guide has been sent to the email address you provided.

This is nice to know I ride my bike 6 miles to work and home about 6 days a week so thank you

I commute to work by bicycle everyday

in Bangkok,Thailand

Comments are closed.